-

Proposal for a visual media exhibition

with the participation of students of the Master of Film at the Dutch Film Academy, Amsterdam -

Get my films

Buy DVDs online at www.momento-films.com -

IZKOR

slaves of memory

Documentary film | 1990 | 97 min | color | 16mm | 4:3 | OV Hebrew ST -

Common Archive Palestine 1948

web based cross-reference archive and production platform

www.commonarchives.net/1948 - Project in progress - -

Montage Interdit [forbidden editing]

With professors Ella (Habiba) Shohat and Robert Stam / Berlin Documentary Forum 2 / Haus der Kulturen der Welt / June 2012 -

Route 181

fragments of a journay in Palestine-Israel

Documentary film co-directed with Michel Khleifi | 2003 | 272 min [4.5H] | color | video | 16:9 | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST

-

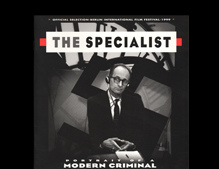

The Specialist

portrait of a modern criminal

Documentary film | 1999 | co-author Rony Brauman | 128 min | B/W | 4:3 | 35 mm | OV German, Hebrew ST -

Jaffa

the orange's clockwork

Documentary film | 2009 | 88 min | color & B/W | 16:9 | Digital video | OV Arabic, Hebrew, English, French ST

-

Montage Interdit

www.montageinterdit.net

Web-based documentary practice. A production tool, archive and distribution device | project in progress

-

Common State

potential conversation [1]

Documentary film | 2012 | 123 min | color | video | 16:9 split screen | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST -

Towards a common archive

testimonies by Zionist veterans of 1948 war in Palestine

Visual Media exhibition | Zochrot Gallery (Zochrot visual media lab) | Tel-Aviv | October 2012 - January 2013

-

I Love You All

Aus Liebe Zum Volk

Documentary film co-directed with Audrey Maurion | 2004 | 89 minutes | b/w & color | 35mm | OV German, French ST

by Eyal Sivan (Berlin Documentary Forum 1 - Magazine)

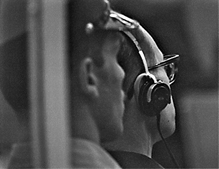

On a chilly spring night of April 1961, the Nazi officer Adolf Eichmann gets taken out from his high security prison in order to attend an extraordinary unofficial and discrete session of the Jerusalem district court where his trial has been taking place since the month of March. Following a request from Eichmann’s lawyer the court convenes to preview the films which the attorney general wished to show during the next day’s public session. Wearing a prison uniform and wool pullover, the defendant Adolf Eichmann enters the dark court and takes his place in the glass booth opposite the cinema screen. The mute scene of the man in his sixties, wearing a homey outfit, staring with curiosity at the images appearing on the screen in front of him, was secretly recorded on video. In fact, Leo T. Hurwitz – the American director in charge of the Eichmann trial multicamera recordings – violated the legal framework of the court’s video recordings and documented the perpetrator Adolf Eichmann as an ordinary silent cinema spectator in his intimacy. Filmed by the Allied forces during the liberation of the Nazi concentration and death camps, the images on the screen were totally new to Eichmann. Hurwitz’s mute scene of Adolf Eichmann, the documentary cinema spectator, tells the initial encounter between the criminal and the image of the crime. In addition to these images previously screened at the 1945–46 Nuremberg Trials (which since then have gained an iconic status of the Holocaust representation) the Israeli attorney general chose to screen to the defendant and the court the short documentary film Nuit et Brouillard (Night and Fog). Produced ten years after the Nuremberg Trials by the French filmmaker Alain Resnais, edited with a text by French author Jean Cayrol and a score by Germancomposer Hanns Eisler, Resnais’ 32-minute film commissioned in 1955 by the French World War II history committee (Comité d’histoire de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale) is the first fictionalised documentary representation of the Nazi concentration and extermination system. As only one of the four cameras installed in the Jerusalem court could be recorded on videotape, Hurwitz decided to trace the images of the spectator. He focused on Adolf Eichmann’s initial discovery of the images rather than on the screened image, privileging the projection rather than the screening. The counter shots, the screened film footage, create (in real time) a confrontation between the Nazi’s gaze and the consequences of his deeds. Eichmann the spectator becomes a witness. Almost five decades later, Resnais’ friend and colleague, the French image-maker Chris Marker, downloads Leo T. Hurwitz’s night screening shots from the Eichmann trial video archives available on the Internet. Chris Marker, Resnais’ assistant on Nuit et Brouillard, synchronizes Hurwitz’s shots with those of Resnais’ film. Re-placing the missing sound and changing the screened images with the equivalent scenes from Renais’ Night and Fog, Marker composes Henchman Glance. Horwitz’s unauthorised images of Eichmann watching Resnais’ Night and Fog, edited by Marker together with the original film’s sound and colour shots are an invitation to experience the destabilising effect of watching the horror with the perpetrator, and through his eyes. The unsigned 32-minute documentary composition Henchman Glance is a paradigmatic representation of the documentary practice question. The observation of the perpetrator, the visual interrogation of the witness of the political evil, the investigationof power and authority, marked the post-World War II documentary cinema. Paradoxically, immediately after the end of the war, documentary moving images seemed to gain both the status of witness and proof. During the Nuremberg Military Tribunals (NMT) staged in Germany in 1945, documentary images were mobilised in order to deliver their truth testimony, to show reality. Staged in order to give an image to the Nazi horror, the cinema screening in court (becoming simultaneously a cinematic object) is a turning point for documentary cinema interrogation. A generation of young filmmakers born between the 1920s and 1930s and having grown up through the war would gradually and by various modes domesticate the documentary cinema in order to interrogate the documentary practice’s potential to produce truth. Suspicious of power and inhibited by the urgent interrogation of authority, challenged by public habits of spectatorship under the shadow of propaganda and the cold war, the post-World War II documentary practitioners forged new modalities of production and distribution, and witnessed the arrival of the TV channels as influential actors. The twenty years that followed the end of World War II led to major aesthetical political debates and experimentation around cinema, documentary practice and language – two decades which became the backdrop for a process of reinvention and emancipation of the documentary moving image. It was a practice expropriated from ruling power and re-appropriated by independent imagesmakers in order to achieve its re-politicisation and apotheosis during the late 1960s and 1970s. In order to tell the story of the regaining of confidence in the documentary image after World War II, this montage is seeking to narrate and review some landmarks of the practice’s history(ies). “Documentary Moments” is a montage born from the desire to observe, to grasp, to historicise and then re-view the documentary gesture. It is a feeling of need to elaborate on the articulation of the documentary film practice as a tool enabling the reading of the image – any image – as image. 1946, the year when the Nuremberg trials were staged in Germany, is designated as the year zero of documentary film practice. The project “Documentary Moments: Renaissance” brings together the ‘classics’ of documentary cinema in an attempt to write the oral history of the post Euro-Genocide (documentary) image. Four takes depict the reinvention of documentar y language and the exploration of its potentialities in the years that followed the war. An historical era during which, being a favourite tool of power, the documentary images were disseminated as a weapon among others. “Take 1” delineates a path toward the seminal Nuit et Brouillard. Several short documentary films produced in the 1940s and 1950s will be screened: Guernica (1950) and Les Statues Meurent Aussi (Statues Also Die, 1953) as well as Henchman Glance with commentaries by cultural historians Adrian Rifkin and Marie-José Mondzain. “Take 2” of “Documentary Moments” is called “Memory of the Future”. It consists of a revisit of the film Chronicle of a Summer (1961). Directed by anthropologist Jean Rouch and sociologist Edgar Morin, Chronicle of a Summer builds truth through constructed or almost fictional situations. When released, it provoked heated debates on the relationship between cinema, reality and truth. In 2007, artists Ayreen Anastas, François Bucher and Rene Gabri unearthed an interview with Edgar Morin, in which he mentioned a cache of original rushes. With the assistance of Françoise Foucault, a former collaborator of Rouch, they succeeded in finding nearly everything that had not been included in the final edit. Shots from the original 16 mm rushes of Chronicle of a Summer and a discussion with Edgar Morin will make up the core of this programme. “Take 3” is entitled “’Direct’, ‘Truth’ and other Myths”. Independent producer and filmmaker Frederick Wiseman’s unswerving interest is to produce direct cinema, a notion refuted by Wiseman himself. Since the mid-1960s, he has scrutinised American life and institutions, revealing the mechanisms of administration and hierarchy. His practice is a benchmark in the entire history of social documentary. Both a school and a genre, Wiseman’s infinitely re-qualified cinema is indispensable in any debate on the potential of the documentary image to produce truth. Significantly, Wiseman declares, “Cinema verité is just a pompous French term that has absolutely no meaning as far as I’m concerned.” A conversation between Frederick Wiseman and film historian Stella Bruzzi is followed by a screening of his film Primate (1974), which presents a scientific study of the physical and mental development of primates, as conducted at Yerkes Primate Research Center. “Take 4” is called “Wartime/War crime”. Filmmaker Marcel Ophuls uses the documentary interview and montage to review and re-edit historical narration, subverting the hegemony of authority and its propaganda image. His epic oeuvre – both in scope and in length – is a landmark of the critical historical essay. By introducing the filmmaker as an actor of history, “where (my) point of view and creativity come in”, he redefines the notion of resistance. A conversation between Marcel Ophuls and Eyal Sivan is followed by a screening of the film The Memory of Justice (1973-1976). The film uses Telford Taylor’s book Nuremberg and Vietnam: An American Tragedy as a point of departure in exploring wartime atrocities and individual versus collective responsibility. Documentary Moments: Renaissance

Take 1 – Towards Night and Fog: Alain Resnais. Thursday June 3, 7 pm

Take 2 – Memory of the Future: Edgar Morin. Friday June 4, 6 pm

Take 3 – ‘Direct ’, ‘Truth’ and other Myths: Frederick Wiseman. Saturday June 5, 4.30 pm

Take 4 – Wartime/War crime: Marcel Ophuls. Sunday June 6, 6 pm