-

Proposal for a visual media exhibition

with the participation of students of the Master of Film at the Dutch Film Academy, Amsterdam -

Get my films

Buy DVDs online at www.momento-films.com -

IZKOR

slaves of memory

Documentary film | 1990 | 97 min | color | 16mm | 4:3 | OV Hebrew ST -

Common Archive Palestine 1948

web based cross-reference archive and production platform

www.commonarchives.net/1948 - Project in progress - -

Montage Interdit [forbidden editing]

With professors Ella (Habiba) Shohat and Robert Stam / Berlin Documentary Forum 2 / Haus der Kulturen der Welt / June 2012 -

Route 181

fragments of a journay in Palestine-Israel

Documentary film co-directed with Michel Khleifi | 2003 | 272 min [4.5H] | color | video | 16:9 | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST

-

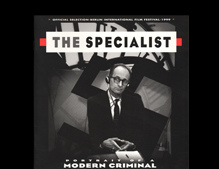

The Specialist

portrait of a modern criminal

Documentary film | 1999 | co-author Rony Brauman | 128 min | B/W | 4:3 | 35 mm | OV German, Hebrew ST -

Jaffa

the orange's clockwork

Documentary film | 2009 | 88 min | color & B/W | 16:9 | Digital video | OV Arabic, Hebrew, English, French ST

-

Montage Interdit

www.montageinterdit.net

Web-based documentary practice. A production tool, archive and distribution device | project in progress

-

Common State

potential conversation [1]

Documentary film | 2012 | 123 min | color | video | 16:9 split screen | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST -

Towards a common archive

testimonies by Zionist veterans of 1948 war in Palestine

Visual Media exhibition | Zochrot Gallery (Zochrot visual media lab) | Tel-Aviv | October 2012 - January 2013

-

I Love You All

Aus Liebe Zum Volk

Documentary film co-directed with Audrey Maurion | 2004 | 89 minutes | b/w & color | 35mm | OV German, French ST

reviews

The image of the orange in history by Bert Rebhandl (culturebase.net)

04.06.2010

The image of the orange in history

by Bert Rebhandl

(culturebase.net)

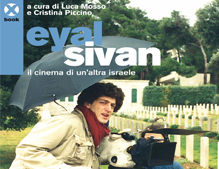

Pick up an orange in the supermarket produce section and it is not unlikely it will be from Israel. The Jaffa name is associated with a rich brand tradition. Over decades, countless shiploads of Jaffa oranges have left Tel Aviv, bound for ports around the world. Behind every brand there is a story. In the case of Jaffa, it is that of Arab-Jewish farming in Palestine, which with the founding of the nation of Israel in 1948 was quietly banished from public memory. In his documentary film “Jaffa, the Orange’s Clockwork,” Eyal Sivan explores the image of the Jaffa orange through the course of its history – from the early days of Zionism up to recent times, in which Israel mutated into an occupying power and people around the world began to boycott its oranges. Today, many regard the documentary filmmaker and author Sivan to be one of the “dissidents” of Israeli cinema.

It is characteristic of Sivan, a Jew critical of his own homeland, that from this seemingly peripheral subject he gains an original perspective on the state of Israel. As early as his first film, “Aqabat Jaber: Passing Through” (1987), compelled by his interest in the living conditions of Arabs who had lost their home, he crossed the political divide to film a Palestinian refugee camp. It was the first political work of this former fashion photographer, who had left Jerusalem for Paris in 1985.

Sivan followed “Aqabat Jaber” in 1991 with “Izkor: Slaves of Memory,” which, drawing on interviews with the philosopher Yeshayahu Leibowitz, grapples with the role the Holocaust played in forging Israel’s national identity. In the 1990s he continued his conversations with Leibowitz with regard to both films, reaffirming his positions on such questions as the right of return for Arabs expelled after 1948, which continues to divide Israeli society.

In the short 1996 documentary “Itsembatsemba – Rwanda One Genocide Later,” Sivan turned his attention to the process of coming to terms with the Rwandan genocide. In significant part, this too was an attempt to place the Holocaust’s exceptional position in the international politics of memory into a broader context, without relativizing it.

With “The Specialist,” made jointly with Rony Brauman in 1997, Sivan gained a wider audience. The film assembles video material from the 1961 Jerusalem trial of the National Socialist war criminal Adolf Eichmann as it examines the term “banality of evil” coined by Hannah Arendt. Sivan is simultaneously concerned with the reconstruction of this key historical moment, the first manifestation of the “transnational historical narrative” that made it possible to view the attempted extermination of the Jews from a perspective not determined exclusively by the history of the Second World War.

Numerous festival invitations and international controversy followed. Sivan was increasingly looked to as an expert in questions of historical archiving and of the official politics of memory. His work on this subject includes the 2004 film montage “I Love You All,” which uses film material from the East German state security service.

In 2002 a film came out that again set debate in motion on the issues that had always been Sivan’s driving concern. For “Route 181: Fragments of a Journey in Palestine-Israel,” he and his Palestinian colleague Michel Khleifi drove along the Israeli-Palestinian border that had been designated by the UN in 1948. This imaginary line, which de facto never took effect, served as a geographical and thematic guide for the filmmakers’ documentation of current conditions in the disputed areas of Palestine. A number of scenes in “Route 181” at least pose the question of a comparison between Israeli policies and the genocidal policies of National Socialist Germany. Claude Lanzmann, the director of “Shoah,” took offense at two scenes that showed a Palestinian barber and railway tracks. In them, Lanzmann saw not only revisionist references to comparable passages in “Shoah,” but also an attack against Jewish victims of the NS extermination campaign.

The controversy remains heated right up to today – support for Sivan’s position from the likes of Jean-Luc Godard and the philosopher Etienne Balibar notwithstanding. At its root, this is a fight over how we come to terms with the past. Sivan opposes the remembering of the Shoah in the way which has become doctrine; in his view, it lends legitimacy to a misguided policy. For this reason, Sivan, along with Avi Mograbi and Amos Gitai, is internationally considered to be one of the “dissidents” of Israeli cinema.

Author: Bert Rebhandl

by Bert Rebhandl

(culturebase.net)

Pick up an orange in the supermarket produce section and it is not unlikely it will be from Israel. The Jaffa name is associated with a rich brand tradition. Over decades, countless shiploads of Jaffa oranges have left Tel Aviv, bound for ports around the world. Behind every brand there is a story. In the case of Jaffa, it is that of Arab-Jewish farming in Palestine, which with the founding of the nation of Israel in 1948 was quietly banished from public memory. In his documentary film “Jaffa, the Orange’s Clockwork,” Eyal Sivan explores the image of the Jaffa orange through the course of its history – from the early days of Zionism up to recent times, in which Israel mutated into an occupying power and people around the world began to boycott its oranges. Today, many regard the documentary filmmaker and author Sivan to be one of the “dissidents” of Israeli cinema.

It is characteristic of Sivan, a Jew critical of his own homeland, that from this seemingly peripheral subject he gains an original perspective on the state of Israel. As early as his first film, “Aqabat Jaber: Passing Through” (1987), compelled by his interest in the living conditions of Arabs who had lost their home, he crossed the political divide to film a Palestinian refugee camp. It was the first political work of this former fashion photographer, who had left Jerusalem for Paris in 1985.

Sivan followed “Aqabat Jaber” in 1991 with “Izkor: Slaves of Memory,” which, drawing on interviews with the philosopher Yeshayahu Leibowitz, grapples with the role the Holocaust played in forging Israel’s national identity. In the 1990s he continued his conversations with Leibowitz with regard to both films, reaffirming his positions on such questions as the right of return for Arabs expelled after 1948, which continues to divide Israeli society.

In the short 1996 documentary “Itsembatsemba – Rwanda One Genocide Later,” Sivan turned his attention to the process of coming to terms with the Rwandan genocide. In significant part, this too was an attempt to place the Holocaust’s exceptional position in the international politics of memory into a broader context, without relativizing it.

With “The Specialist,” made jointly with Rony Brauman in 1997, Sivan gained a wider audience. The film assembles video material from the 1961 Jerusalem trial of the National Socialist war criminal Adolf Eichmann as it examines the term “banality of evil” coined by Hannah Arendt. Sivan is simultaneously concerned with the reconstruction of this key historical moment, the first manifestation of the “transnational historical narrative” that made it possible to view the attempted extermination of the Jews from a perspective not determined exclusively by the history of the Second World War.

Numerous festival invitations and international controversy followed. Sivan was increasingly looked to as an expert in questions of historical archiving and of the official politics of memory. His work on this subject includes the 2004 film montage “I Love You All,” which uses film material from the East German state security service.

In 2002 a film came out that again set debate in motion on the issues that had always been Sivan’s driving concern. For “Route 181: Fragments of a Journey in Palestine-Israel,” he and his Palestinian colleague Michel Khleifi drove along the Israeli-Palestinian border that had been designated by the UN in 1948. This imaginary line, which de facto never took effect, served as a geographical and thematic guide for the filmmakers’ documentation of current conditions in the disputed areas of Palestine. A number of scenes in “Route 181” at least pose the question of a comparison between Israeli policies and the genocidal policies of National Socialist Germany. Claude Lanzmann, the director of “Shoah,” took offense at two scenes that showed a Palestinian barber and railway tracks. In them, Lanzmann saw not only revisionist references to comparable passages in “Shoah,” but also an attack against Jewish victims of the NS extermination campaign.

The controversy remains heated right up to today – support for Sivan’s position from the likes of Jean-Luc Godard and the philosopher Etienne Balibar notwithstanding. At its root, this is a fight over how we come to terms with the past. Sivan opposes the remembering of the Shoah in the way which has become doctrine; in his view, it lends legitimacy to a misguided policy. For this reason, Sivan, along with Avi Mograbi and Amos Gitai, is internationally considered to be one of the “dissidents” of Israeli cinema.

Author: Bert Rebhandl