-

Proposal for a visual media exhibition

with the participation of students of the Master of Film at the Dutch Film Academy, Amsterdam -

Get my films

Buy DVDs online at www.momento-films.com -

IZKOR

slaves of memory

Documentary film | 1990 | 97 min | color | 16mm | 4:3 | OV Hebrew ST -

Common Archive Palestine 1948

web based cross-reference archive and production platform

www.commonarchives.net/1948 - Project in progress - -

Montage Interdit [forbidden editing]

With professors Ella (Habiba) Shohat and Robert Stam / Berlin Documentary Forum 2 / Haus der Kulturen der Welt / June 2012 -

Route 181

fragments of a journay in Palestine-Israel

Documentary film co-directed with Michel Khleifi | 2003 | 272 min [4.5H] | color | video | 16:9 | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST

-

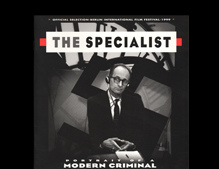

The Specialist

portrait of a modern criminal

Documentary film | 1999 | co-author Rony Brauman | 128 min | B/W | 4:3 | 35 mm | OV German, Hebrew ST -

Jaffa

the orange's clockwork

Documentary film | 2009 | 88 min | color & B/W | 16:9 | Digital video | OV Arabic, Hebrew, English, French ST

-

Montage Interdit

www.montageinterdit.net

Web-based documentary practice. A production tool, archive and distribution device | project in progress

-

Common State

potential conversation [1]

Documentary film | 2012 | 123 min | color | video | 16:9 split screen | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST -

Towards a common archive

testimonies by Zionist veterans of 1948 war in Palestine

Visual Media exhibition | Zochrot Gallery (Zochrot visual media lab) | Tel-Aviv | October 2012 - January 2013

-

I Love You All

Aus Liebe Zum Volk

Documentary film co-directed with Audrey Maurion | 2004 | 89 minutes | b/w & color | 35mm | OV German, French ST

Some forty years after the publication of Hannah Arendt’s controversial book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, the Israeli-born filmmaker Eyal Sivan released his documentary film The Specialist, explicitly referring to Arendt’s work. Sivan took archive footage filmed in 1961, during the trial of Nazi criminal Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem, and edited it to present a cinematic articulation of Arendt’s book. The film discusses the fundamental flaws in the way the trial was conducted as well as the nature of Eichmann’s crimes.

This article analyzes Sivan’s use of narrative, editing, visual, and auditory stylistic devices to expose the way the trial was used by the Zionist movement and to challenge its active role within Zionist collective memory. If interpreted as part of a more general post-Zionist artistic and intellectual production, The Specialist could be understood as deconstructing the accused / accuser dichotomy, and suggesting that the accusers and their contemporary heirs might themselves be guilty of some of the charges made against the defendant.

The Nazi criminal Adolf Eichmann was caught on May 11, 1960 by three

Mossad agents while alighting from a bus, returning from a working day

in Buenos Aires, Argentina. The Eichmann trial began in Jerusalem eleven months later; it lasted eight months and resulted in the death sentence. Eichmann was hanged on May 31, 1962, after his appeal was denied. Hannah Arendt, a German-born philosopher sent by The New Yorker to review the trial, published her book, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, which was based on her remarks from the trial, in 1963. The Hebrew translation of this book, however, was completed only in 2000, a year after the appearance of The Specialist, a film by the Israeli filmmaker Eyal Sivan, which was inspired by Eichmann in Jerusalem. Raising some controversial questions about the conducting of the trial and the judicial decisions, the book ignited an emotional debate. The Jewish philosopher’s skepticism regarding the common

description of Eichmann as a blood-thirsty antisemitic monster, and her criticism of the decision to hold the trial in Jerusalem, earned her many opponents among her own people. Thus, for instance, Gershom Scholem, the prominent Kabbalah scholar, denounced Arendt as “heartless,” “malicious,” and lacking in “love of the Jewish people.” The controversy around the book is evidently the main cause for the 40 years’ delay in its translation.

However, I do not enter here the bitter controversy regarding Arendt’s

view, as it belongs within the context of the historical or the judicial discourse. This article, rather, discusses two main issues in regard to Sivan’s film. I shall present first Arendt’s main arguments concerning Eichmann’s trial, followed by a discussion of the way they are cinematically articulated and elaborated in The Specialist. In light of this approach, I shall stress the linkage between the film and the book’s translation and the historic-ideological conditions under which both appeared.

Banal Murderous Specialism as a Universal Crime

In Arendt’s view, the basic fault of the trial was its ideological oversight of

the horrifying essence of Eichmann’s crime. Arendt repeatedly stresses that Eichmann was primarily a criminal against humanity, and not only an enemy of the Jewish people. She claims that his main motivation, which had driven him through his murderous career, was not that of pure antisemitism, but a mixture of obedience, dullness, and a desire to satisfy his supervisors. She contends that Eichmann’s arbitrary path was guided not by hatred of Jews but by the banal ambition of a mediocre man.

Although Arendt frequently disputes the judges’ opinion, it is worth noting that she agrees with the death sentence imposed on Eichmann. Although she tends to accept Eichmann’s claim that he only obeyed orders and did not independently set them, she argues that since he could have avoided his mission without any risk to himself, and because he made no effort to mitigate the harm he caused, he deserved the death penalty.

Arendt illustrates Eichmann’s banal mode of thought through analysis of

his surprising declaration that “he had lived his whole life according to Kant’s moral precepts, and especially according to Kantian definition of duty”(pp. 135–136). When asked by Judge Raveh for the meaning of this statement, Eichmann surprisingly came up with an approximately correct definition of the categorical imperative: “I meant by my remark about Kant that the principle of my will must always be such that it can become the principle of general laws” (p. 136).

Arendt argues that, although distorted, Eichmann’s reliance upon Kant

is highly illustrative: Kant maintained that a rational subject who complies

with the categorical imperative must “[a]ct only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.”

Arendt notes that this distorted formula of the imperative is equivalent to

that of Hans Frank, the Nazi governor-general of Poland: “Act in such a way that the Führer, if he knew your action, would approve it” (p. 136).

She claims that this view—“that to be law-abiding means not merely to obey the laws but to act as though one were the legislator of the law that one obeys”—was common in Germany in those days (p. 137). Instead of adhering to his own “practical reason,” exceeding the current local law and acting in accordance with principles that are appropriate to be the principles of the universal law, Eichmann interpreted his blind obedience to the Nazi law as an exemplary implementation of the categorical imperative. Thus, the Kantian argument in favor of identification with the idea that the law is based upon was twisted and replaced with identification with the person that stands behind the law.

According to Arendt, this mode of thought guided Eichmann’s administrative obedience, which caused the death of millions. In her view, it was this banality of evil—and not an uncontrollable antisemitic hatred—that drove Eichmann to commit his horrible crimes, out of respect for the law. That law commonly stated as “Thou shalt not kill” was replaced in Hitler’s Germany with the demand “Thou shalt kill” (p. 150).

Arendt considers Eichmann’s frequent use of dull clichés as another expression of his banality of thought. She claims that the common feature of those clichés was not their antisemitic nature, but their ability to elicit a sense of elation in Eichmann. Once he declared, “I will jump into my grave laughing, because the fact that I have the death of five million Jews... on my conscience gives me extraordinary satisfaction” (p. 46), and on another occasion he stated, “I shall gladly hang myself in public as a warning example for all anti-Semites on this earth” (p. 54), apparently without noting the acute contradiction between these two proclamations.

The judges found Eichmann to be a kind of cunning liar, a clever felon

who pretended to be a fool, using hollow phrases in an attempt to cover up the crimes he had committed in full awareness of their moral meaning. Arendt finds the judges’ view in regard to his clever slyness to have been faulty, considering his ludicrousness, his obsessive use of infuriating clichés, and the damage he caused himself due to his inability to recall certain crucial facts that could have helped him in handling the accusations with which he was faced (p. 49).

Trying Eichmann in Jerusalem

Arendt criticizes those who denied Israel’s right to judge Eichmann on its own territory by claiming that Eichmann’s activities had taken place throughout occupied Europe and thus should be under the jurisdiction of an international court. “Once the Jews had a territory of their own, the State of Israel, they obviously had as much right to sit in judgment on the crimes committed against their people as the Poles had to judge crimes committed in Poland” (p. 259), she claims. Despite its legitimacy, however, Arendt maintains that the decision to hold the trial in Jerusalem, and some of the judicial conclusions, denied the universal principle of justice in the name of the local Zionist justice. She strongly criticizes the Israeli court for missing what she defines as the essence of Eichmann’s crimes. In her view, the Eichmann trial should have been grounded on the understanding that the Nazi crimes against the Jewish people were primarily a crime against humanity.

The Nazi regime clearly persecuted the Jews out of a deliberate policy of

extermination of entire populations. Nevertheless, Arendt notes that the Nazi “administrative massacres” were focused not only on entire nations or races but also on German groups of the physically and mentally disabled, or patients determined as “incurably ill” (p. 288). She strongly maintains that the attempt to eliminate entire populations should be considered not merely as an extremely severe case of murder, but as a new type of crime. “It is an attack upon human diversity as such, that is, upon a characteristic of the ‘human status’ without which the very words ‘mankind’ or ‘humanity’ would be devoid of meaning,” she claims (pp. 268–269). In her view, the Holocaust was in effect a Nazi crime against humanity that “was perpetrated upon the body of the Jewish people” (p. 269). And since the new crime violated not only the inner political

balance, but also the international order, only an international tribunal would have been appropriate to apply the rigor of the law (p. 269).

In Arendt’s view, the decision to hold the trial in Israel was based on the

Jewish people’s concept of their own history. They conceived the Nazi crimenot as an unprecedented type of genocide, but as a recent and most dreadful stage in the continuum of persecutions that the Jews have suffered since the early days of their history. Arendt claims that the fact that the Eichmann trial was set in this context is the main source for its injustices:

"This misunderstanding, almost inevitable if we consider not only the facts of Jewish history but also, and more important, the current Jewish historical selfunderstanding, is actually at the root of all the failures and shortcomings of the Jerusalem trial. None of the participants ever arrived at a clear understanding of the actual horror of Auschwitz, which is of a different nature from all the atrocities of the past, because it appeared to prosecution and judges alike as not much more than the most horrible pogrom in Jewish history. (p. 267)"

Thus, in Arendt’s view the contextualization of Eichmann’s crimes within

the history of antisemitic persecutions was not only judicially flawed, but also damaging. Trying these crimes before a tribunal that represented one nation only, “minimized” their monstrous nature and reduced the ability to present them as a general concern for mankind as a whole. It constituted the missing of an opportunity to establish the sentence for Eichmann’s crimes as an international precedent that could hopefully prevent future similar crimes (pp. 272–273).

In examining the reasons for this failure, Arendt blames Ben-Gurion for

“invisibly stage-managing the proceedings” (pp. 4–5) according to his own current interests. In her opinion, the prominent Zionist leader had sought to design the Eichmann trial as a show-trial in which antisemitism as a whole would be brought to justice. He wished to exploit political benefits by emphasizing the connections between the Nazis and certain Arab rulers, conceived by him as the contemporary avatar of the eternal oppressor of the Jews (p. 10).

Although the judges in general managed to resist the external pressure

and did not follow the attempts of the prosecution to portray Eichmann as

a “perverted sadist,” Arendt claims that nevertheless they were finally found “conspicuously helpless” when they were confronted with the inevitable task of “understanding the criminal whom they had come to judge” (p. 276). In her view, it was precisely the normality of Eichmann that should have been stressed by the tribunal as the source and the prominent characteristic of his crimes, and also as an important factor in the decision regarding his sentence.

She claims that facing the inclination of the prosecution to present Eichmann from the idiosyncratic Jewish perspective as an antisemitic abnormal phenomenon who willingly took part in the most horrible of pogroms, it was the highest duty of this court to recognize him rather as a universal criminal of a new type, and to sentence him as such. Because such a criminal, who blatantly obeys illegal orders under circumstances that make it impossible for him to know or feel that he is doing wrong, poses a risk not only to the Jewish people but also to the whole of mankind,

"[t]he trouble with Eichmann was precisely that so many were like him, and that the many were neither perverted nor sadistic, that they were, and still are, terribly and terrifyingly normal. From the viewpoint of our legal institutions and our moral standards of judgment, this normality was much more terrifying than all the atrocities put together. (p. 276)"

However, as for the sentence handed down, Arendt rejects Eichmann’s

claim of diminished guilt in that his role had been an accident and that almost anybody could have taken his place. “[E]ven if eighty million Germans had done as you did, this was not an excuse,” writes Arendt and adds: “In politics obedience and support are the same.” Carrying out a policy of mass murder is equivalent to the active support of this crime, which should be penalized by death (pp. 278–279).

Narrative Vertigo as Subversion of the Zionist Chronology

Some forty years after Eichmann in Jerusalem saw light, it was adapted by Eyal Sivan, an Israeli filmmaker who lives in Paris, as the basis for his film The Specialist. Sivan, who is also known for his decisive moral critique on the Zionist ideology and practice, explicitly mentions Arendt’s controversial book as a source of inspiration in the credits of the film. In fact, in The Specialist Sivan uses cinematic-linguistic tactics of deconstruction and reconstruction to give Arendt’s claims a filmic articulation.

This film disassembles both the conventional narrative structure of cinematic and televisional courtroom texts, and the specific structure of the

Eichmann trial. He avoids the narrative device of adhering to the chronology and the dramas of the trial, which is common in fact-based or fictive courtroom dramas and documentaries (e.g., the chronological documentaries about Eichmann trial: Verdict for Tomorrow [1961] and The Trial of Adolf Eichmann [1997]; fact-based courtroom dramas regarding the Holocaust such as Nuremberg [2000] and Mishpat Kastner aka The Kastner Trial [1994]; trial documentaries such as Brother’s Keeper [1992] and Un coupable idéal aka Murder on a Sunday Morning [2001]; and other well-known features like Accused [1988], A Few Good Men [1992], Philadelphia [1993] and Amistad [1998]).

Such a narrative choice enables the filmmaker to exploit fully the dramatic potential that is naturally embodied in a structure of the trial: a gradual exposure of information, progressive build-up of tension, and an impressive dramatic and moral conclusion.

Rather than exploiting these “dramatic treasures,” however, Sivan chooses

to present a prominently disrupted and incomplete chronology of Eichmann’s trial. The original order of the trial was as follows:

1) Reading of the Indictment—Eichmann trial begins (April 11, 1961);

2) The prosecution pleads its case and summons witnesses; 2) The defense

presents its case and examines the accused; 3) Eichmann is cross-examined by the prosecution; 4) The defense attorney, Dr. Robert Servatius, briefly reexamines the accused; 5) Eichmann is examined by the judges; 6) Summations; 7) After four months, the court reassembles for pronouncement of the judgment (December 11, 1961); 8) The death sentence is pronounced (December 15, 1961).

Sivan was presumably aware of the order of the trial, but his narrative

outstandingly denies its logic. The film opens with the seventh session and

concludes with a sequence taken from Eichmann’s cross-examination in Session 95 (13 July 1961) out of 121. Shots that were taken during later sessions (e.g., 97, 106) are intercut in the course of the film. Examination of a randomly picked series of scenes located towards the end of the film illustrates Sivan’s denial of the logic of the trial. Following are the sessions ordered according to the sequence of these scenes, which document them: session 95 (Eichmann’s cross-examination); sessions 51–52 (testimony of Pinhas Freudiger); session 106 (examination of Eichmann by Judge Raveh); session 93 (Eichmann’s cross-examination); session 87 (examination of Eichmann by his defense attorney); session 95 (Eichmann’s cross-examination).

This distorted chronology occurs not only at the level of entire scenes but

also on the editorial scale within the scene. The editing sometimes violates

the chronological ordering by juxtaposing fragments from different stages of the trial. Sivan was recently blamed by Hillel Tryster, the director of Steven Spielberg’s Jewish Film Archive, for “fraud, forgery and falsification” due to a series of editorial “distortions.” According to Tryster, the original footage of the trial was manipulatively edited by Sivan in a way that insults the witnesses and is unfaithful to the testimonies. He notes some examples: the artificial juxtaposition of Hausner’s question about the absence of resistance in the extermination

camps with the silence of the witness Avraham Lindwasser that was taken from another testimony; the artificial insertion of audience laugher into several shots; and the elliptical editing that led to the distortion of the

testimony of Pinhas Freudiger, a leader of the Orthodox community in Hungary.

Regardless of the moral aspects of these editorial choices, it is clear that

Sivan intentionally denies the original order of the trial.

Moreover, the last stages of the trial—the pronouncement of judgment

and the death sentence—are completely absent in the film, as are other relevant events such as the appeal to the Supreme Court of Israel and the execution (nor are these facts mentioned in any way). The absence of such important events, which are used as significant dramatic elements in the conventional courtroom drama, clearly violates the common narrative pattern of representation of trials in film and television. Sivan’s “relinquishing” these dramatic climaxes is certainly not accidental. He chooses this way in order to manifest his resistance to the logic that the Zionist concept of the trial is based upon.

In addition to distortion of the chronology of the trial, the film also creates

a sort of “historical vertigo” by avoiding relevant information regarding

Israeli and international public opinion about the case and omission of the

specific dates for its opening and the conclusion. Indications of time are presented in the film only once: three signs noting May 8, 1961 (session 30), June 7 (session 68–69), and July 14 (session 97) are shown successively, seemingly arbitrarily located in the film. At this point Sivan uses the sound-bridge device: the sound from the successive shot of a testimony invades the shot of the last time-mark. Importantly, the date mentioned on the last slide and the date of this actual testimony do not fit.

Mr. Georges Wellers gave his testimony on May 9, 1961, while in session 97, held on July 14, 1961, Eichmann was crossexamined on a completely different issue. The juxtaposition of these three different time markers in such a deceptive manner and the fact that they are sole and isolated, invert their original function: instead of clearly indicating the location of the trial events on the historical timeline, they contribute nothing to the understanding of the context or even harm it, and thus ironically serve as signs of disorientation.

This historical decontextualization is a cinematic device used by Sivan

to offend against the Zionist interpretation, which considers the Eichmann

trial as a paragon of justice in terms of the right finally gained by the Jews

to sentence to death one of their antisemitic deadly foes. By concealing the

historical context of the trial, Sivan reduces the ability to present it as part of the successive time-line outlined by Zionism. He disrupts its patriotic moral meaning as a Zionist lesson of history, as decisive evidence that only a Jewish justice that is supported by the power of a Jewish State can finally effectively fight against the ancient phenomenon of antisemitism. Just as Arendt rejects the context attributed by the Zionist state to Eichmann’s crimes within the history of antisemitism, so too does Sivan deny the context of the whole trial in the Zionist super-narrative.

The Trial as a Play Whose End is Known

The series of testimonies of hundreds of prosecution witnesses (90 of whom were Holocaust survivors who had been held in Nazi captivity), unfolding their tales of horror, lasted 62 sessions—more than half of the total number of sessions. A large portion of the testimonies was not directly concerned with Eichmann or with the activities he had been involved in. The prosecution presented these testimonies as background material that was gradually assembling to form a “general picture.” The judges were uncomfortable with the long discussions about matters that had no direct connection with the crimes of the accused, but they did not halt the emotional testimonies out of understandable humane considerations. However, the presiding judge, Moshe Landau,

did rebuke the Attorney General several times, reminding him that “we are

not drawing pictures here” (p. 120). Landau concluded the testimony of the witness Abba Kovner5 with another admonition to the prosecution:

"We have heard shocking things here, in the language of a poet, but I maintain that in many parts of this evidence we have strayed far from the subject of this trial. . . . It is your [Hausner’s] task to prepare the witness, to explain matters to him, and to eliminate everything that is not relevant to the trial. . . . I regret that I have to make these remarks, after the conclusion of evidence such as this."

Arendt describes the atmosphere in this phase of the testimony as one of “a mass meeting, at which speaker after speaker does his best to arouse the

audience” (p. 121). Although she claims that all in all the trial never totally

descended into a theatre play, she argues that it was designed by the Israeli

authorities as a moral spectacle:

"Whoever planned this auditorium in the newly built Beth Ha’am, the House of the People . . . had a theater in mind, complete with orchestra and gallery, with proscenium and stage, and with side doors for the actors’ entrance. Clearly, this courtroom is not a bad place for the show trial David Ben-Gurion, Prime Minister of Israel, had in mind when he decided to have Eichmann kidnapped. . . . (p. 4)"

In this performance Eichmann was supposed to play the well-defined role

that had been designated for him by the Zionist leadership. That expectation stemmed from the anticipation that the trial would encourage Jews to recognize the value of Zionism, and also raise an international sense of guilt (or, as Ben-Gurion put it: “We want the nations of the world to know . . . and they should be ashamed” [p. 10]).

Arendt maintains that Hausner’s attempts to present Eichmann as a monstrous offspring of the ancient antisemitic dynasty of Pharaoh in Egypt and Haman the Agagite were not only pathetic but also judicially flawed:

"[I]t was clearly at cross-purposes with putting Eichmann on trial, suggesting that perhaps he was only an innocent executor of some mysteriously foreordained destiny or, for that matter, even of anti-Semitism, which perhaps was necessary to blaze the trial of “the bloodstained road traveled by this people” to fulfill its destiny. (p. 19)"

However, as mentioned earlier, it was not only the prosecution’s perceived faults or the negation of the right of the accused to be judged only for his own crimes that bothered Arendt. It was mainly the attempts to contextualize Eichmann’s case exclusively within the Zionist super-narrative—attempts that were served by the performative characteristics of the trial—that concerned the Jewish philosopher. In her view, the inclination to turn the trial into a Zionist show-trial thwarted the chance of ever getting to the roots of the universal nature and severity of Eichmann’s crimes.

Sivan fully adopts Arendt’s insight and expends considerable efforts on

critically exposing the ostentatious aspects of the trial. This trend is manifested early in the opening credits of the film. The names of the trial’s key figures are presented in the same manner as movie stars’ names are presented beside their roles: “Adolf Eichmann—The Accused”, “Robert Servatius—Defense Attorney”, “Gideon Hausner—Attorney General,” etc. This sequence is concluded with the credit “In Film by Rony Brauman and Eyal Sivan,” as if Eichmann, the attorneys, and the judges all belonged to Sivan’s cast.

The sequence that follows the opening credits shows a montage of a series

of Hausner’s extroverted body gestures and theatrical hand movements.

Arendt does not hide her aversion to Hausner’s style of litigation. She defines his opening address as “bad history and cheap rhetoric” (p. 19) and criticizes his behavior in the trial:

"The latter’s [Ben-Gurion’s] rule, as Mr. Hausner is not slow in demonstrating, is permissive; it permits the prosecutor to give press-conferences and interviews for television during the trial . . . and even “spontaneous” outbursts to reporters in the court building—he is sick of cross-examining Eichmann who answers all questions with lies; it permits frequent side glances into the audience, and the theatrics of more than ordinary vanity, which finally achieves its triumph in the White House with a compliment on “a job well done” by the President of the United States. (p. 6)"

The “condensed theatrical montage” of Hausner in the opening sequence

of The Specialist clearly echoes Arendt’s criticism about the style of the Attorney General. By giving filmic manifestation to her claim, Sivan stresses another aspect of the showiness of the trial.

The emphasis on the performative characteristics of the Eichmann trial is

a consistent thread running through the film, articulated in varied cinematic expressions. Thus, for instance, considerable technological efforts were invested in creating a digital image of the reflection of the trial audience on the glasswalls of the booth in which Eichmann was placed during the trial. These efforts indicate the importance of a key-element of a show trial—the constant presence of an audience—in the eyes of the filmmakers.

Throughout the film a great deal of attention is paid to the technical preparations towards the court sessions: it presents a meticulous depiction of the setting up of the microphones, the arrangement of documents in court, the entry of the judges, etc. The accompaniment of these images by the disharmonious sounds of musical instruments being tuned serves to create an analogy between the courtroom and the concert hall—the preparations for the judicial session are paralleled with the preparations for a musical show.

The sound-effect of sonic feedback is also associated with the technical

preparations for a public performance. When Eichmann describes the operations of Section IVB4, the mobile killing units, Hausner impatiently asks him to talk for once without “all the documents and books.”

Reprimanded, Eichmann apologizes and sits down to the vocal accompaniment of a prominent dissonant feedback. In the spirit of Arendt’s viewpoint, this sound-effect can be interpreted as a sonic metaphor. The sonic feedback is an irritating tone caused by a recursive process in which an input sound that is received by the receiver is amplified, received, and amplified again by the same receiver, and so forth. In light of Arendt’s view that the Eichmann trial was designed to convict an accused who had been convicted in advance, one may indicate an analogy between the trial and the sonic feedback. The trial serves as an amplifier to the voices of the accusers—the Zionist authorities. It is designed to receive and amplify their accusations, but in doing so the Zionist show-trial exceeds its aim to the extent of dissonance.

In another sequence near the end of the first hour of the film, several testimonies of Holocaust survivors in the trial are juxtaposed successively while the images are visually reframed and intentionally garbled. These visual effects serve to produce the effect of an old television broadcast, and consequently present the testimonies in the context of a mass media performance. In emphasizing the formal aspects of this sequence at the expense of its content, Sivan echoes Arendt’s claim about the preference of the Zionist exemplary value for “drawing the general picture” at the expense of judicial interests.

The filmed testimonies are thematically categorized according to the

filmmaker’s view as follows: witnesses take their place on the witness stand; setting up the microphones; oaths on the witness stand; discussions about the transports; introduction of Holocaust objects: yellow Stars of David, shoes, documents etc; description of the crimes committed by the S.S.; stories about meetings with Eichmann; witnesses in difficult moments: evidence on nightmares, emotional outbursts, and weeping. The sequence concludes with the aforementioned rebuke of Hausner by Judge Landau: “In many parts of this evidence we have strayed far from the subject of this trial.” Similarly to Arendt, Sivan finds Landau’s rebuke an appropriate summation to this sequence of testimonies, stressing its irrelevancy to the case. But Sivan also gives this claim a filmic manifestation: by thematically categorizing the testimonies he critically

emphasizes their role as links in the argumentation chain of the prosecution.

He fragments them and stresses their common rhetoric characteristics

at the expense of their unique content as he draws the outlines of the “general picture”—a picture that found favor neither with Arendt nor with the judges.

As in the case of his narrative choices, Sivan again adopts a strategy of

avoiding emotional immersion in the drama of the horrifying Holocaust testimonies in favor of formation of a “critical distance.” This estrangement enables examination of the rhetoric function of the testimonies, regardless of their powerful emotional load. He also uses this strategy in an earlier sequence, which presents the screening in the courtroom of footage documenting dreadful Nazi crimes. Sivan is focused on the way the horror is presented—the act of the screening—and not on the horror itself. The screen in the dark courtroom is not shot frontally and the footage is not edited into the film as one might expect. The dreadful images, accompanied by Hausner’s commentary, are barely seen, reflected on the glass walls of Eichmann’s booth or shot by a camera, which is set almost perpendicularly to the screen surface.

Thus, inspired by Arendt, Sivan critically directs our attention to the

performative aspects of the prosecution’s actions rather than an emotional

focus on their content. His refusal of the drama—not a trivial choice for a

filmmaker—is also a protest against the dramatic interpretation given to this trial in the Zionist super-narrative. Sivan rather emphasizes the dissonances resulted from the bias to set the trial as a public account of antisemitism from time immemorial. His consistent exposure of the performative characteristics of the trial is in line with Arendt’s argument that to a great extent the trial was a fore-designed show with a known end and lesson, which dissonantly echo the Zionist perspective of Eichmann’s crimes and disregard other crucial meanings. Thus, Sivan reflects Arendt’s criticism of the setting of Eichmann’s case exclusively in the antisemitic context as the source for the inability of the tribunal to fulfill its high duty and get at the of the universal essence of the crimes of the accused.

The Bureaucratic Obsession

Sivan seems to fully adopt Arendt’s claim that Eichmann committed his

dreadful crimes out of a banal normality, which is actually “much more terrifying than all atrocities put together” (p. 276). He cinematically portrays him as a pedantic clerk whose obsession with detail is a threatening normality. While Hausner is reciting numbers and letters mentioning the units of the Nazi extermination apparatus, Eichmann is shown punctiliously writing down the details. Hausner’s voice becomes a monotonic echo, which is replaced with the amplified sound of a pen writing. The frame is also visually distorted. These effects repeat later in the film when Hausner indicates the origin and destination of the transport trains, and in another scene when Eichmann leaves his cell and uses a wall map in an attempt to answer the questions of the Attorney General. By cinematically manipulating the documented moments of Eichmann’s “reunion” with details and lists, Sivan illustrates Eichmann’s enthusiasm

for registration and administration—his “bureaucratic obsession.”

By systematically distorting the sound and the image at these moments, he

signs them as special events for Eichmann, who expresses his obsession with bureaucratic details, a truly horrifying normality.

Arendt finds this obsession to be at the root of Eichmann’s murderous efficiency.

Combined with his blind obedience it comprises the essence of banal

evil. Loyal to his distorted interpretation of the Kantian categorical imperative, the pedantic bureaucrat suppresses any sign of individual conscience, devoting himself totally to his faith in law and authority. In one scene Eichmann is asked about his responsibility for orders that bear his signature on a document of section IVB4. “It is a common bureaucratic formulation,” says Eichmann, “my signature has nothing

to do with the person Eichmann.”

According to Arendt, Eichmann sought to conceal himself under a mountain of bureaucracy in order to escape his deserved punishment for his responsibility for the crimes committed under his authority (p. 290). The film cinematically expresses this idea: Eichmann’s words are heard once again as his figure gradually fades out from the glass cell, leaving behind a desk with documents and two guards with a frozen expression.

Arendt’s central argument about the subjugation of the individual conscience at the service of the authorities is echoed in a sequence in which the judges question Eichmann about the functioning of his conscience during the war. They were interested in his statement according to which, at the Wannsee Conference (in which the Nazis planned the “final solution”—a program for extermination of the Jews in Europe), he said that he felt like Pontius Pilate washing his hands in innocence due to his understanding that he had only to follow the instructions set by his supervisors.