-

Proposal for a visual media exhibition

with the participation of students of the Master of Film at the Dutch Film Academy, Amsterdam -

Get my films

Buy DVDs online at www.momento-films.com -

IZKOR

slaves of memory

Documentary film | 1990 | 97 min | color | 16mm | 4:3 | OV Hebrew ST -

Common Archive Palestine 1948

web based cross-reference archive and production platform

www.commonarchives.net/1948 - Project in progress - -

Montage Interdit [forbidden editing]

With professors Ella (Habiba) Shohat and Robert Stam / Berlin Documentary Forum 2 / Haus der Kulturen der Welt / June 2012 -

Route 181

fragments of a journay in Palestine-Israel

Documentary film co-directed with Michel Khleifi | 2003 | 272 min [4.5H] | color | video | 16:9 | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST

-

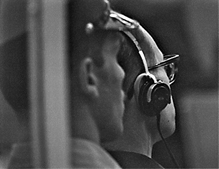

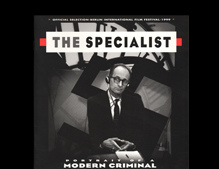

The Specialist

portrait of a modern criminal

Documentary film | 1999 | co-author Rony Brauman | 128 min | B/W | 4:3 | 35 mm | OV German, Hebrew ST -

Jaffa

the orange's clockwork

Documentary film | 2009 | 88 min | color & B/W | 16:9 | Digital video | OV Arabic, Hebrew, English, French ST

-

Montage Interdit

www.montageinterdit.net

Web-based documentary practice. A production tool, archive and distribution device | project in progress

-

Common State

potential conversation [1]

Documentary film | 2012 | 123 min | color | video | 16:9 split screen | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST -

Towards a common archive

testimonies by Zionist veterans of 1948 war in Palestine

Visual Media exhibition | Zochrot Gallery (Zochrot visual media lab) | Tel-Aviv | October 2012 - January 2013

-

I Love You All

Aus Liebe Zum Volk

Documentary film co-directed with Audrey Maurion | 2004 | 89 minutes | b/w & color | 35mm | OV German, French ST

press

Atrocity Exhibitions by J. Hoberman (The Village Voice)

12.04.2000

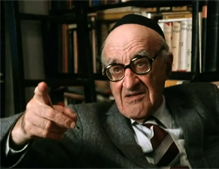

The real Adolf Eichmann—or at least his televisual form—is currently on view in The Specialist, an austere and fascinating documentary fashioned by Israeli director Eyal Sivan from the 500 hours of video footage shot by Leo Hurwitz during the trial.

More than the miniseries Holocaust or the Oscar-winning Schindler's List, the spectacle of Eichmann in Jerusalem introduced America—and the world—to the facts of what was, for the first time, referred to as the Holocaust. Even then, many intellectuals understood the trial's fundamental purposes to be the legitimization of Israeli authority and the creation of a Holocaust narrative. Harold Rosenberg ascribed to it "the function of tragic poetry, that of making the pathetic and terrifying past live again in the mind."

Here, the Eichmann trial itself is that pathetic and terrifying past. A performance-documentary set in a hall of mirrors, The Specialist—like the movie fashioned from the army-McCarthy hearings, Point of Order—is about history as it is structured in court and mediated by the camera. The credits suggest a cast of actors; the first few shots are of the empty seats and stage. Excavating the event as theater, Sivan is less interested in giving voice to the many witnesses against Eichmann or showing the atrocity footage entered as evidence than in demonstrating how this evidence functioned in the trial. The material has been digitally enhanced so that the image of the audience is reflected on Eichmann's protective glass booth, and the frequent, sometimes violent, crowd reactions are now audible.

The greatest emphasis is on Eichmann's performance. His peculiar half-smile as he listens through a headset to the testimony against him is unnerving and disarming. (You should have seen the balding, bespectacled clerk—a self-identified "specialist" in forced emigration—when he was costumed in his SS uniform of absolute power.)

Eichmann is clever enough to suggest that he is really a Zionist and stupid enough to insist that he improved conditions on the transports to Treblinka. He is fastidious in his language, precise in his evasions, anxious to seem reasonable, deferential to authority. This born flunky always stands to speak—one assumes he also clicks his heels—an appropriate tactic for a man who, arguing for his life, claims only to have followed his superiors' orders.

Sivan further accentuates the differing agendas of the judges, some interrogating Eichmann directly, and the show's real director, prosecutor Giddeon Hausner. Aggressively trying to break down a criminal bureaucrat who had no official function apart from his mandated task of facilitating the extermination of Jews, Hausner grows increasingly sarcastic. When cornered, however, Eichmann holds his ground: "I refuse to reveal my inner feelings," he sulks, taking refuge in his own enigma as the empty suit of institutionalized evil.