-

Proposal for a visual media exhibition

with the participation of students of the Master of Film at the Dutch Film Academy, Amsterdam -

Get my films

Buy DVDs online at www.momento-films.com -

IZKOR

slaves of memory

Documentary film | 1990 | 97 min | color | 16mm | 4:3 | OV Hebrew ST -

Common Archive Palestine 1948

web based cross-reference archive and production platform

www.commonarchives.net/1948 - Project in progress - -

Montage Interdit [forbidden editing]

With professors Ella (Habiba) Shohat and Robert Stam / Berlin Documentary Forum 2 / Haus der Kulturen der Welt / June 2012 -

Route 181

fragments of a journay in Palestine-Israel

Documentary film co-directed with Michel Khleifi | 2003 | 272 min [4.5H] | color | video | 16:9 | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST

-

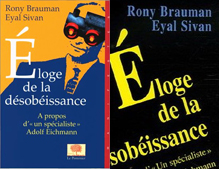

The Specialist

portrait of a modern criminal

Documentary film | 1999 | co-author Rony Brauman | 128 min | B/W | 4:3 | 35 mm | OV German, Hebrew ST -

Jaffa

the orange's clockwork

Documentary film | 2009 | 88 min | color & B/W | 16:9 | Digital video | OV Arabic, Hebrew, English, French ST

-

Montage Interdit

www.montageinterdit.net

Web-based documentary practice. A production tool, archive and distribution device | project in progress

-

Common State

potential conversation [1]

Documentary film | 2012 | 123 min | color | video | 16:9 split screen | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST -

Towards a common archive

testimonies by Zionist veterans of 1948 war in Palestine

Visual Media exhibition | Zochrot Gallery (Zochrot visual media lab) | Tel-Aviv | October 2012 - January 2013

-

I Love You All

Aus Liebe Zum Volk

Documentary film co-directed with Audrey Maurion | 2004 | 89 minutes | b/w & color | 35mm | OV German, French ST

press

Refugees watch themselves in award-winning film (Palestine Refugees Today)

01.10.1987

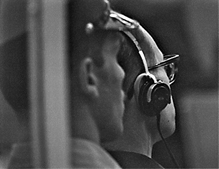

On a sweltering July evening, some 200 people jammed into a small hall near Jericho in the West Bank for a free film show. This was no ordinary summer cinema event, however. The film being shown was about the people watching it: the residents of Aqabat Jaber camp for Palestine refugees.

And this was no ordinary commercial film, either. Aqabat Jabr: Vie de passage (Passing Through) is an 86-minute French-made documentary which won this year’s first prize at the prestigious Cinéma du Réel documentary film festival at the Pompidou Centre in Paris. The first film by 23-year-old director Eyal Sivan, it has just been screened twice at the Jerusalem Film Festival and, to show his appreciation to the camp residents, Mr. Sivan personally brought it to the Aqabat Jabr youth activities centre to show it to them under UNRWA’s auspices.

The film show itself turned into something of a media event, as foreign journalists and television crews turned up to record the impressions of the crowd watching the film on two video screens.

The reaction was enthusiastic. The audience cheered and laughed at seeing themselves and their neighbours appear on screen. But the serious message of the film was not lost in the excitement. The theme of the film is that the 3,000 residents of Aqabat Jabr lead mostly unfulfilling lives in an inhospitable environment while waiting for a just solution of the problem that first brought some 35,000 Palestine refugees to this harsh patch of desert in the Jordan Valley some 38 years ago. In the 1967 occupation of the West Bank, thousands of refugees from the area lied across the river Jordan and only a few thousand now remain.

“This is an accurate representation of life in the camp,” said 24-year-old Imad after watching the film. “It showed the hard situation we’re living in.”

In the film, the refugees of Aqabat Jabr, young and old, men and women, tell their own stories directly to the camera. From the few men who have work to the women filling out their days with household chores to the old men sitting in cafés, the story they tell is the same: Even after all these years life in the camp is viewed as a temporary phase pending their return to ancestral villages on the coastal plain.

“Back there, in my village, life was prosperous and abundant,” says one man interviewed in the film. “I was happy. I worked my land … it was paradise.”

In a review of the film, the renowned French photojournalist Henri Cartier-Bresson wrote: “This film goes beyond politics. It is about a country people confined for the past 38 years in refugee camps, about the humiliation of being severed from their land, their orchards, their villages. Nothing happens in the film because nothing happens in their lives. Endlessly waiting, some still cling to the hope of returning one day to their land. It is not a silent film. It cries out in its simplicity wrenching the heart.”

Eyal Sivan and his crew spent 12 days filming in Aqabat Jaber in November 1986. To get the full feel of life there, the crew lived in the camp, in the midst of a severely cold and wet winter. They filmed interviews with 28 camp residents, all of whom appear in the film (their names and those of their native villages appear in the titles at the end). Reviewers have remarked at the spontaneity and naturalness, which the filmmakers succeeded in eliciting from subjects who could understandably have felt reluctant to expose their misery and distress to the world.

Mr. Sivan said the positive reaction of the camp residents to the film delighted him as much as winning the grand prize in Paris. Returning to the camp, he was greeted as a friend. After the showing, he stayed on to chat with people about their reactions, and was then invited to spend the night in the camp, which he did. Arrangements are now being pursued for showing a shortened television version of the film in a number of countries.

And this was no ordinary commercial film, either. Aqabat Jabr: Vie de passage (Passing Through) is an 86-minute French-made documentary which won this year’s first prize at the prestigious Cinéma du Réel documentary film festival at the Pompidou Centre in Paris. The first film by 23-year-old director Eyal Sivan, it has just been screened twice at the Jerusalem Film Festival and, to show his appreciation to the camp residents, Mr. Sivan personally brought it to the Aqabat Jabr youth activities centre to show it to them under UNRWA’s auspices.

The film show itself turned into something of a media event, as foreign journalists and television crews turned up to record the impressions of the crowd watching the film on two video screens.

The reaction was enthusiastic. The audience cheered and laughed at seeing themselves and their neighbours appear on screen. But the serious message of the film was not lost in the excitement. The theme of the film is that the 3,000 residents of Aqabat Jabr lead mostly unfulfilling lives in an inhospitable environment while waiting for a just solution of the problem that first brought some 35,000 Palestine refugees to this harsh patch of desert in the Jordan Valley some 38 years ago. In the 1967 occupation of the West Bank, thousands of refugees from the area lied across the river Jordan and only a few thousand now remain.

“This is an accurate representation of life in the camp,” said 24-year-old Imad after watching the film. “It showed the hard situation we’re living in.”

In the film, the refugees of Aqabat Jabr, young and old, men and women, tell their own stories directly to the camera. From the few men who have work to the women filling out their days with household chores to the old men sitting in cafés, the story they tell is the same: Even after all these years life in the camp is viewed as a temporary phase pending their return to ancestral villages on the coastal plain.

“Back there, in my village, life was prosperous and abundant,” says one man interviewed in the film. “I was happy. I worked my land … it was paradise.”

In a review of the film, the renowned French photojournalist Henri Cartier-Bresson wrote: “This film goes beyond politics. It is about a country people confined for the past 38 years in refugee camps, about the humiliation of being severed from their land, their orchards, their villages. Nothing happens in the film because nothing happens in their lives. Endlessly waiting, some still cling to the hope of returning one day to their land. It is not a silent film. It cries out in its simplicity wrenching the heart.”

Eyal Sivan and his crew spent 12 days filming in Aqabat Jaber in November 1986. To get the full feel of life there, the crew lived in the camp, in the midst of a severely cold and wet winter. They filmed interviews with 28 camp residents, all of whom appear in the film (their names and those of their native villages appear in the titles at the end). Reviewers have remarked at the spontaneity and naturalness, which the filmmakers succeeded in eliciting from subjects who could understandably have felt reluctant to expose their misery and distress to the world.

Mr. Sivan said the positive reaction of the camp residents to the film delighted him as much as winning the grand prize in Paris. Returning to the camp, he was greeted as a friend. After the showing, he stayed on to chat with people about their reactions, and was then invited to spend the night in the camp, which he did. Arrangements are now being pursued for showing a shortened television version of the film in a number of countries.