-

Proposal for a visual media exhibition

with the participation of students of the Master of Film at the Dutch Film Academy, Amsterdam -

Get my films

Buy DVDs online at www.momento-films.com -

IZKOR

slaves of memory

Documentary film | 1990 | 97 min | color | 16mm | 4:3 | OV Hebrew ST -

Common Archive Palestine 1948

web based cross-reference archive and production platform

www.commonarchives.net/1948 - Project in progress - -

Montage Interdit [forbidden editing]

With professors Ella (Habiba) Shohat and Robert Stam / Berlin Documentary Forum 2 / Haus der Kulturen der Welt / June 2012 -

Route 181

fragments of a journay in Palestine-Israel

Documentary film co-directed with Michel Khleifi | 2003 | 272 min [4.5H] | color | video | 16:9 | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST

-

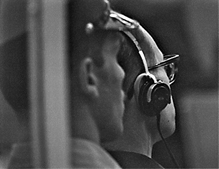

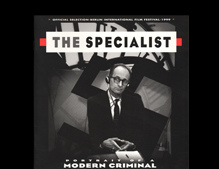

The Specialist

portrait of a modern criminal

Documentary film | 1999 | co-author Rony Brauman | 128 min | B/W | 4:3 | 35 mm | OV German, Hebrew ST -

Jaffa

the orange's clockwork

Documentary film | 2009 | 88 min | color & B/W | 16:9 | Digital video | OV Arabic, Hebrew, English, French ST

-

Montage Interdit

www.montageinterdit.net

Web-based documentary practice. A production tool, archive and distribution device | project in progress

-

Common State

potential conversation [1]

Documentary film | 2012 | 123 min | color | video | 16:9 split screen | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST -

Towards a common archive

testimonies by Zionist veterans of 1948 war in Palestine

Visual Media exhibition | Zochrot Gallery (Zochrot visual media lab) | Tel-Aviv | October 2012 - January 2013

-

I Love You All

Aus Liebe Zum Volk

Documentary film co-directed with Audrey Maurion | 2004 | 89 minutes | b/w & color | 35mm | OV German, French ST

Representing the Eichmann Trial 10 years of controversy around The Specialist

By Rebecka Thor

M.A. Thesis for Liberal Studies, The New School for Social Research in New York.

Advisor: Andreas Kalyvas, Assistant Professor of Political Science, The New School

for Social Research in New York

Reader: Juliane Rebentisch, Professor of Philosophy, Goethe University in Frankfurt am Main. A special thanks to Eyal Sivan.

Contents:

1. Disruptive Narratives.............................................................................................3

2. The Trial of Adolf Eichmann...................................................................................8

3. The Making and Archiving of the Material..............................................................12

4. Responsibilities towards the Archive and Representations of Documentary Images...16

5. To Show Instead of Telling...................................................................................32

6. Consequences of Representation..........................................................................49

7. Bibliography........................................................................................................67

8. Filmography........................................................................................................72

9. Appendix: Interview with Eyal Sivan.....................................................................73

1. Disruptive Narratives

“Butcher, butcher!”

The words are heard before we see the man shouting. The film cuts to the

audience; two guards drag their struggling charge out of the courtroom by his arms. A buzz spreads through the audience, all are turned towards him, one of the judges calls for order, and cut – the moment is over and a new scene begins. These few seconds in the very beginning of film The Specialist: Portrait of a Modern Criminal, directed by Eyal Sivan and released in 1999, exemplify the controversy that has followed the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem 1961. The trial itself has become emblematic for various reasons: it was the only time Israel convicted a somewhat high-ranking Nazi; it was the first time survivors publicly testified; the entire trial was videotaped and broadcast on both television and radio around the world. The aftermath, too, has been marked by much contentiousness. Two years after the trial, Hannah Arendt published an account of it in her book Eichmann in Jerusalem: a Report on the Banality of Evil, and in so doing forever damaged her relationship to the international community of Jews in exile and posed her as the controversial thinker she would be known as.

The historical backdrop of Arendt’s book is necessary for understanding the issues at the core of the discussions of The Specialist. The film’s main critic, Hillel Tryster, the former director of the Steven Spielberg Jewish Film Archive – the archive responsible for the filmed trial material – refers to the historian and scholar of Shoah, Yehuda Bauer, and claims that Bauer suggested that a film based upon Arendt’s book “cannot be worthy of analysis.”1 Such harsh judgment upon both the film and the book, suggests just how complicated these discussions are. Hillel Tryster believes, however, that the film merits attention for two reasons: first, since it has gained such public recognition and second, since it provides a rare type of case study since most of the material comes from the same archival source.2 However, as we will see, there seems to be more than this at stake in his criticism.

Over a quarter of a century later, an Israeli filmmaker would consider Arendt’s work and contribute his own perspective to the Eichmann trial. Filmmaker Eyal Sivan came to the subject in a roundabout way. In 1990, Sivan was doing research for a film at the Spielberg Archive in Jerusalem, when he discovered a shelf filled with tapes marked, in English, “The Eichmann Trial.” After some research he found out that the reels held actual footage from the trial. He contacted Rony Brauman, at that time the director of Doctors Without Borders, and told him about his discovery. Brauman gave Sivan Hannah Arendt’s book and thereafter they decided to make a film of the material, based upon book.3 They wrote the script together and Sivan directed it. Sivan and Brauman worked with the material from a clearly defined perspective: they wanted to tell the story of the perpetrator, in accordance with the account given by Arendt. They chose to structure the film into 13 chapters, divided by black frames, which creates visual ruptures.5 Each chapter, or sequence, has a particular focus, signaled in its title, and the different nature of the titles is apparent in the first two; “The trial opens,” which is rather neutral, and the second, “A Specialist in compulsory emigration who enjoys his work.”

One’s of the film’s most striking features involves its point-of-view – a great number of shots are focused on Eichmann: listening to translations, scribbling down notes, organizing his papers, or trying to answer questions posed to him. Besides Eichmann, the prosecutor, attorney general Gideon Hausner plays a leading role and the image often returns to him, reacting to Eichmann’s statements. The judges are frequently shown reprimanding witnesses and spectators; they provide a notion of a proper conduct and they appear to be the reason that the trial does not decline to total chaos. For most part, the film moves rapidly, cutting quickly between perspectives and incidents, but unbroken shots lasting several minutes serve to give a few episodes special emphasis: filmed material from the camps flicker in the darkened courtroom during one long, uncomfortable sequence, and a few survivors give testimony in a series of short shots; the viewer is shown witnesses after witness.Sivan did not edit the material with the sole aim of constructing a narrative; instead, he broke up the chronology. Besides making a new storyline, he manipulated the material heavily, both by traditional means of editing and by reinforcing shadows, adding reflections and sometimes by impairing the quality of the original images. His reworking doesn’t stop there – since the sound of the video was inferior, the filmmakers chose to work with the audio recorded for radio instead, and then synchronized it with the filmed material. The audio is not only synchronized with the images, but the voices are repeated at times, sometimes blurred, and sounds are added at times other than when they originally appeared.