-

Proposal for a visual media exhibition

with the participation of students of the Master of Film at the Dutch Film Academy, Amsterdam -

Get my films

Buy DVDs online at www.momento-films.com -

IZKOR

slaves of memory

Documentary film | 1990 | 97 min | color | 16mm | 4:3 | OV Hebrew ST -

Common Archive Palestine 1948

web based cross-reference archive and production platform

www.commonarchives.net/1948 - Project in progress - -

Montage Interdit [forbidden editing]

With professors Ella (Habiba) Shohat and Robert Stam / Berlin Documentary Forum 2 / Haus der Kulturen der Welt / June 2012 -

Route 181

fragments of a journay in Palestine-Israel

Documentary film co-directed with Michel Khleifi | 2003 | 272 min [4.5H] | color | video | 16:9 | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST

-

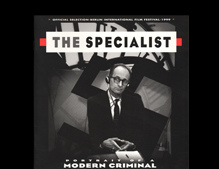

The Specialist

portrait of a modern criminal

Documentary film | 1999 | co-author Rony Brauman | 128 min | B/W | 4:3 | 35 mm | OV German, Hebrew ST -

Jaffa

the orange's clockwork

Documentary film | 2009 | 88 min | color & B/W | 16:9 | Digital video | OV Arabic, Hebrew, English, French ST

-

Montage Interdit

www.montageinterdit.net

Web-based documentary practice. A production tool, archive and distribution device | project in progress

-

Common State

potential conversation [1]

Documentary film | 2012 | 123 min | color | video | 16:9 split screen | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST -

Towards a common archive

testimonies by Zionist veterans of 1948 war in Palestine

Visual Media exhibition | Zochrot Gallery (Zochrot visual media lab) | Tel-Aviv | October 2012 - January 2013

-

I Love You All

Aus Liebe Zum Volk

Documentary film co-directed with Audrey Maurion | 2004 | 89 minutes | b/w & color | 35mm | OV German, French ST

reviews

Greater Palestine: Matching Demography, Geography, and Heart (The Arab World Geographer / Le Géographe du monde arabe 8, no 3 (2005)

08.03.2005

Greater Palestine:

Matching Demography, Geography, and Heart

by Sharif S. Elmusa

Political Science Department, The American University in Cairo, 113 Kasr El-Aini Street, Cairo, Egypt

Demography matters. Witness South Africa and Iraq, where blacks won majority rule and where Shiites and Kurds are asserting their demographic weight. People, like buildings and roads, like swimming pools and tele- phone towers, are facts on the ground. Today there are more than 8 million Palestinians in Greater Palestine,2 the Palestine that existed before Winston Churchill split it by fiat into Palestine and Transjordan. Their number should double, in 30 years or so, to 16 million. They will need housing; they will need food and roads; they will need water and health care. They will become more educated and more productive. They will fight fiercely for a state in which they have equal citizen- ship rights, as the last 100 years have taught us. I submit here that the site of this state must be re-imagined, and that Greater Palestine is the only viable alternative for the three major ethnic communities that live in it: East Jorda- nians, Jews, and Palestinians.

The Israelis have been obsessed with demography. This obsession has led them to fix their gaze eastward, where they wish the Palestinians to vanish. Build a wall, they have told themselves lately, so you can’t see them, so you can secure Israel behind the 1949 armistice line, grab more land, found more Jewish settlements, expand those that exist already, and further fragment Palestinian space.

That way you also carry the battle into the enemy’s remaining meagre territory in the West Bank. Soon the pressure cooker will cause the Palestinians to evaporate, to become, indeed, a people without a land, as Max Nordau, the Hungarian-born Zionist orator, infamously called them (cited in Childers 1971, 168). My mother, who hailed from the village of Abbasiyya (now the town of Yehud), once told me that a Jewish man from a settlement of Petah Tekfa said to her and a group of villagers in Hebrew-accented Arabic, “Ya khabibi inta rayekh yiji youm tihij ib-balalsh” (“A day will come, love, when you’ll do the pilgrimage to Mecca for free”). In the highly revealing film Route 181, jointly directed by an Arab and a Jew, Michel Khleifi and Eyal Sivan (2004), the randomly interviewed Jews, almost without exception, advocate the expulsion of the Palestinians. It is not a wordless wish, as Erskine Childers (1971)called the Zionist desire to expel the Palestinians, but a loud, emphatic, contemp- tuous one. Eviction is not an easy act to implement; the Palestinians would resist it, and the Jordanians too.

Where would the Palestinians go? To Transjordan; that is, across the Jordan River. And what would happen then along the new, long front? Would the Palestinians look west and be stricken with historical amnesia? Would they forget their land and their houses, their hills and their sea? Would they give up al-Aqsa mosque and the church of the Nativ- ity and the Holy Sepulchre? Or would perpet- ual warfare between two irreconcilable foes be the outcome?

This is for prophets to fathom; I am a political scientist with a limited horizon. I am reluctant to bring up the idea of ethnic cleans- ing; talking too often about an unspeakable subject can render it normal, thinkable, if not inevitable. The topic of expulsion should remain taboo, spoken of or imagined only with gravity, with a sense of the forbidden. I bring it up because it happened twice before, in 1948 and in 1967, and because not much has changed in the Zionist vision of the Pales- tinians. The Likud Party, in cooperation with Labor, has largely prepared the strategic ground for another exodus, if not in one wave, then gradually, by haemorrhage. The game of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza is over. The Road Map is an illusion. Presi- dent Mahmoud Abbas, the rationalist “engi- neer of Oslo,” should draw the sobering, logical conclusions. Otherwise, he may find himself before long the political loner he once was.

Politically and culturally, the Palestini- ans constitute a fairly homogenous nation. In spite of Israel’s effort to splinter them into an ever-expanding number of categories— Christians, Druze, Muslims, Gazans, Jerusalemites, Jerichoites, residents of area A, B, or C, displaced persons,3 and refugees—the Palestinians share a strong sense of common identity, solidified in their long defence against the Zionist and Israeli onslaught. They have accumulated rich polit- ical experience and developed, under highly unfavourable circumstances, a civil society and para-state institutions that, imperfect as they are, could form the institutional nucleus of a viable state. They would not be, as is often the case, a state trying to forge a nation from a multiplicity of identities, a state- nation, but a nation fashioning a state. What excludes the possibility of a viable state is the fragmented and vulnerable geography that Israel has left them with.

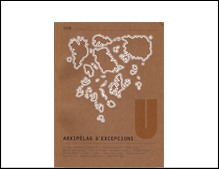

I will not dwell on this geography: the history of its making and its outline are well known to anyone acquainted with the conflict. The long-term Israeli policy of frag- menting the Palestinian territory has reached a new zenith. What remains today is a land archipelago, comprised of isolated islands, Bantustans, cages—call them what you will. They are discontinuous geographies, and they can be linked to one another only through the menace of Israeli-controlled roads and checkpoints. Jewish settlements in the West Bank, intentionally situated at higher elevations, dominate, physically and

symbolically, Palestinian towns and villages. The Gaza Strip itself is a cage, encircled by a fence on three sides and an Israeli-patrolled sea on the fourth, and is cut off from the West Bank. The medieval wall, constructed by the government of Ariel Sharon and declared ille- gal by the International Court of Justice in The Hague, only exacerbates the situation. It may help to protect Israelis from Palestinian violence, but it has exposed Palestinians even further to Israel’s insatiable appetite for land.

Palestinians have already lost more land and orchards as a consequence of the wall. The fragmentation and isolation of their commu- nities have been aggravated. In short, the Palestinians have become caught in a fishnet of Jewish settlements, bypass roads, check- points, and military patrols—walled in and walled out. Fear, insecurity, and a tremendous waste of time are their daily lot. With a state like this, who needs apartheid?

Fragmentation and severe restrictions on the mobility of people and goods have turned the Palestinian economy into a series of micro-economies attached to the Israeli econ- omy. Israeli control over international ports prevents direct linkage of Palestinian markets to Arab and international markets, except through Israeli mediation. A Palestinian state would thus be missing a critical component of statehood: a unified national market joined directly to external markets. A viable state cannot evolve without such a market.

Why did Israel force the Palestinians into this corner? Why did it keep expanding settle- ments and building bypass roads after Oslo? Why did it continue its tight control over the international ports and impede the movement of goods to and from Jordan? Why did it refuse to build a safe passage between Gaza and the West Bank? Why did it, during the pre-Oslo negotiations held in Washington, D.C., stubbornly refuse to demarcate the borders of the settlements and agree to a functional role over them, as the Palestinian delegation headed by Dr. Haidar Abd Al- Shafi had consistently demanded? There is only one explanation: Israel has never accepted the idea of a viable, sovereign Pales- tinian state.

We must recall that before the 1991 Madrid conference Israel had traditionally rejected the idea of a Palestinian state on the grounds that it would be unviable. In an attempt to rebut this thesis, and shortly before the conference, the Institute of Palestine Studies in Washington, published a mono- graph by economist George Abed, The Economic Viability of a Palestinian State. Abed argued that a Palestinian state in the entire West Bank and Gaza would be viable, given that certain economic and political conditions were fulfilled. If the viability of a Palestinian state was contested before Oslo, when Jewish settlements were more sparse than today and the bypass roads and wall were not yet built, surely the debate now has been laid to rest. Israel used what was meant to be a transitional period to Palestinian statehood to render such a state all but impossible. Forget about the “generous offer” of Prime Minister Ehud Barak to President Yasser Arafat at Camp David, for it meant that Israel would take away only a bit more land on top of the 78% of Palestinian land it had come to control after 1948 and would remain the virtual gatekeeper of the borders of any Palestinian state. Forget, too, about differ- ences between Labor and Likud. Construc- tion of Jewish settlements and land seizure was even greater under Labor than under Likud. Shimon Peres, ever the wolf in sheep’s clothing, rescued Prime Minister Ariel Sharon at critical moments whenever the latter found himself constricted in political bottlenecks. The major political forces in Israel want the Palestinians out.

What, then, is to be done?

Even a viable state in the West Bank and Gaza, I think, would not resolve the Palestin- ian Question. We would still be left with the Palestinians who are Israeli citizens, unable to be integrated into a state that insists on being a “Jewish state.” There is not only the Palestinian Question; the Jewish Question, too, still lingers on. And there would be Pales- tinian refugees who legitimately demand the right to return to the territory from which they were evicted. Israel exhibits no sign of consenting to such a demand. That would leave us in Greater Palestine with the Jordan- ian Question, too. For if the refugees remain in Jordan, East Jordanians, whose identity the Jordanian monarchy fostered by pitting them against the Palestinians, would be afraid that sooner or later the Palestinians would take hold of the reins of power. The establishment of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza would intensify their apprehension. The threat of instability would be ever present in the kingdom.

The Palestinians nation has fallen a great fall, and the time has come to put it together again. The Palestinians need to do something that has not been done before: they must tap their demographic advantage. Oslo demobi- lized the Palestinians outside, and Israel’s recent disengagement from Gaza will slowly demobilize its population. Years of isolation under Israel’s dominion tied the West Bank elite to Israeli and Western counterparts, perhaps more than to the Palestinians outside. The segment of the PLO that entered the West Bank and Gaza got busy consolidating its position and ignored the diaspora. “Realist” politicians and intellectuals from both groups began to find it easy to bargain away the right of return of the Palestinian refugees in the naive, if not self-serving, belief that such a give-away would win them a state.

Why should the people who constitute the majority in Greater Palestine be without a state, dispossessed and oppressed by Israel and made sub-citizens by successive Jordan- ian regimes? The time has come for a new vision and a commensurate strategy that would mobilize the Palestinians in Israel, the West Bank and Gaza, and Jordan to create a single state in Greater Palestine that would include themselves, East Jordanians, and Jews. The Palestinians have consistently acquiesced and diminished their aspirations, while the Zionist movement and Israel have inflated theirs. They have been too polite, too soft in their demands. Their adversaries thought and acted out the outrageous and the unthinkable. The Palestinians need now to think out of the box, out of the fishnet, out of the cage.

A trinational state in Greater Palestine (a mutually acceptable name for the state could be agreed on through discussion) has many advantages over the other theoretical alterna- tives: East Jordanian, Jewish, and Palestinian states; a binational state in Western Palestine and an East Jordanian state; or a Jewish state and a Palestinian-Jordanian state in Transjor- dan, the West Bank, and Gaza, as existed between 1948 and 1967.

It would be large enough for everybody; no one has to be squeezed out. It would allow people to move into places where their spirit, their heart, or their pocket feels at home. The right of return of the Palestinian refugees would become largely superfluous. The Jews would live in Eretz Israel, the Palestinians in Greater Palestine, and East Jordanians in Jordan, and those who hail from cities like Hebron and Nablus could, if they so wish, reunite with their roots. With my sincere admiration for Jordan’s historical heritage, I should think that it would be loftier for East Jordanians to belong to a state that encom- passes Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and Nazareth. For millennia, Jews coexisted with Arabs and Muslims and thrived economically and culturally in their midst. The creation of Israel disrupted an admirable, long-shared cultural history, as Ammiel Alcalay wonderfully demonstrates in his After Jews and Arabs: Remaking Levantine Culture. It relegated Israel’s “Oriental Jews” to an inferior position relative to that enjoyed by Jews of European descent. Anti-Semitism is a European demon. Why has Zionism chosen to make Jews feel that they belong more to the cultures of their oppressors and annihilators than to those in which they lived fairly amicably? Not least of the virtues of a triethnic state, a large popula- tion means a large market, nothing to scoff at in today’s highly competitive world economy. Shimon Peres propagandized after Oslo for a New Middle East. The current Bush adminis- tration introduced to the agenda a Greater Middle East. Why not start more modestly, with Greater Palestine?

Of course, there are many obstacles and deep-rooted resentments. Israelis, it will be said, will not accept such a seemingly radical suggestion. True, but when in 1974 Yasser Arafat proposed before the UN General Assembly a democratic secular state in West- ern Palestine, Israel said that this was a disguised plan for its destruction. Neither are there many takers in Israel today for the bina- tional state idea that is increasingly gaining support among Palestinian intellectuals. The creation of a unitary state in Greater Palestine is no different in its requisites than that of a bi-ethnic state in Western Palestine, and it has the advantage of not leaving the Palestinian refugees out in the cold or Jordan unstable. Both are historic projects and require much thought, planning, organization, and persuasion.

The vision of a single state in Greater Palestine could come to fruition only through a strategy of Palestinian mass mobilization, non-violence, and dialogue with the other two communities. Violence must be relegated to the dustbin of history. The Palestine Libera- tion Organization (PLO) needs to reconsti- tute itself into a revitalized and vital Palestine Reunification Organization (PRO). A new leadership must emerge, and the old thinking must be jettisoned.

This applies to Israel as well. The course it has pursued is one-eyed (my apologies to the one-eyed). It places too much faith in force and the power of arms, and it suffers from an unhealthy dose of hubris. It may have won Israel a dunam here and a dunam there, but it has embroiled it in interminable warfare. There are no signs that this will change in the foreseeable future. The Hashemites began their career on a high note of pan-Arabism, which has shrivelled to the parochial and divisive “Jordan first.” They and Zionism divided up Greater Palestine and undertook to suppress Palestinian national- ism. In the process they created a deep Pales- tinian–East Jordanian cleavage that keeps the two peoples suspicious of each other. But both they and the Israelis are still in denial, believing that somehow, someday, they can contain the Palestinians. They both need to see this approach for the mirage that it is. They made a formal peace with each other, and now they must both do the same with the Palestinians.

The Palestinians committed their own share of mistakes along the way, and were not entirely blameless. The time has come for them to get out of the tunnel in which the big news has been the next date on which Sharon will refuse to meet Abu Ammar or Abu Mazen. A mini-state never inspired the Pales- tinian collective; how could a state comprised of fragments? The Palestinians need a new source of energy, a new vision. When Jews were debating the boundaries of Palestine early in the 20th century, an extreme Zionist, whose name I cannot recall at the moment, said that the Jordan River did not divide the two banks, it united them. I agree with this insight, absent the man’s bigotry. A single state in Greater Palestine is the sane alterna- tive to internecine conflict and despair, for all its inhabitants.

Notes

1The author was a member of the Palestinian delegation in the Land and Water Working Group in the 1993 bilateral negotiations with Israel held in Washington, D.C.

2Roughly 2.7 million in the West Bank, 1.3 million in Gaza, 1.3 million in Israel, and 3.25 million in Jordan (or 60 % of the total population, which is the commonly cited ratio). These figures are based on the depart- ment of vital statistics in each entity.

3Refugees of the 1967 war.

References

Abed, G. 1990. The Economic Viability of a Palestinian State. Washington, D.C.: Insti- tute of Palestine Studies.

Alcalay, A. 1993. After Jews and Arabs: Remak- ing Levantine culture. Minneapolis: Univer- sity of Minnesota Press

Childers, E. 1971. The worldless wish: From citi- zens to refugees. In The transformation of Palestine: Essays on the origin of the Arab- Israeli conflict, ed. I. Abu-Lughod, 165-202. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Khleifi, M., and Sivan, E. 2004. Route 181 frag- ments of journey to Palestine, Israel

Matching Demography, Geography, and Heart

by Sharif S. Elmusa

Political Science Department, The American University in Cairo, 113 Kasr El-Aini Street, Cairo, Egypt

Demography matters. Witness South Africa and Iraq, where blacks won majority rule and where Shiites and Kurds are asserting their demographic weight. People, like buildings and roads, like swimming pools and tele- phone towers, are facts on the ground. Today there are more than 8 million Palestinians in Greater Palestine,2 the Palestine that existed before Winston Churchill split it by fiat into Palestine and Transjordan. Their number should double, in 30 years or so, to 16 million. They will need housing; they will need food and roads; they will need water and health care. They will become more educated and more productive. They will fight fiercely for a state in which they have equal citizen- ship rights, as the last 100 years have taught us. I submit here that the site of this state must be re-imagined, and that Greater Palestine is the only viable alternative for the three major ethnic communities that live in it: East Jorda- nians, Jews, and Palestinians.

The Israelis have been obsessed with demography. This obsession has led them to fix their gaze eastward, where they wish the Palestinians to vanish. Build a wall, they have told themselves lately, so you can’t see them, so you can secure Israel behind the 1949 armistice line, grab more land, found more Jewish settlements, expand those that exist already, and further fragment Palestinian space.

That way you also carry the battle into the enemy’s remaining meagre territory in the West Bank. Soon the pressure cooker will cause the Palestinians to evaporate, to become, indeed, a people without a land, as Max Nordau, the Hungarian-born Zionist orator, infamously called them (cited in Childers 1971, 168). My mother, who hailed from the village of Abbasiyya (now the town of Yehud), once told me that a Jewish man from a settlement of Petah Tekfa said to her and a group of villagers in Hebrew-accented Arabic, “Ya khabibi inta rayekh yiji youm tihij ib-balalsh” (“A day will come, love, when you’ll do the pilgrimage to Mecca for free”). In the highly revealing film Route 181, jointly directed by an Arab and a Jew, Michel Khleifi and Eyal Sivan (2004), the randomly interviewed Jews, almost without exception, advocate the expulsion of the Palestinians. It is not a wordless wish, as Erskine Childers (1971)called the Zionist desire to expel the Palestinians, but a loud, emphatic, contemp- tuous one. Eviction is not an easy act to implement; the Palestinians would resist it, and the Jordanians too.

Where would the Palestinians go? To Transjordan; that is, across the Jordan River. And what would happen then along the new, long front? Would the Palestinians look west and be stricken with historical amnesia? Would they forget their land and their houses, their hills and their sea? Would they give up al-Aqsa mosque and the church of the Nativ- ity and the Holy Sepulchre? Or would perpet- ual warfare between two irreconcilable foes be the outcome?

This is for prophets to fathom; I am a political scientist with a limited horizon. I am reluctant to bring up the idea of ethnic cleans- ing; talking too often about an unspeakable subject can render it normal, thinkable, if not inevitable. The topic of expulsion should remain taboo, spoken of or imagined only with gravity, with a sense of the forbidden. I bring it up because it happened twice before, in 1948 and in 1967, and because not much has changed in the Zionist vision of the Pales- tinians. The Likud Party, in cooperation with Labor, has largely prepared the strategic ground for another exodus, if not in one wave, then gradually, by haemorrhage. The game of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza is over. The Road Map is an illusion. Presi- dent Mahmoud Abbas, the rationalist “engi- neer of Oslo,” should draw the sobering, logical conclusions. Otherwise, he may find himself before long the political loner he once was.

Politically and culturally, the Palestini- ans constitute a fairly homogenous nation. In spite of Israel’s effort to splinter them into an ever-expanding number of categories— Christians, Druze, Muslims, Gazans, Jerusalemites, Jerichoites, residents of area A, B, or C, displaced persons,3 and refugees—the Palestinians share a strong sense of common identity, solidified in their long defence against the Zionist and Israeli onslaught. They have accumulated rich polit- ical experience and developed, under highly unfavourable circumstances, a civil society and para-state institutions that, imperfect as they are, could form the institutional nucleus of a viable state. They would not be, as is often the case, a state trying to forge a nation from a multiplicity of identities, a state- nation, but a nation fashioning a state. What excludes the possibility of a viable state is the fragmented and vulnerable geography that Israel has left them with.

I will not dwell on this geography: the history of its making and its outline are well known to anyone acquainted with the conflict. The long-term Israeli policy of frag- menting the Palestinian territory has reached a new zenith. What remains today is a land archipelago, comprised of isolated islands, Bantustans, cages—call them what you will. They are discontinuous geographies, and they can be linked to one another only through the menace of Israeli-controlled roads and checkpoints. Jewish settlements in the West Bank, intentionally situated at higher elevations, dominate, physically and

symbolically, Palestinian towns and villages. The Gaza Strip itself is a cage, encircled by a fence on three sides and an Israeli-patrolled sea on the fourth, and is cut off from the West Bank. The medieval wall, constructed by the government of Ariel Sharon and declared ille- gal by the International Court of Justice in The Hague, only exacerbates the situation. It may help to protect Israelis from Palestinian violence, but it has exposed Palestinians even further to Israel’s insatiable appetite for land.

Palestinians have already lost more land and orchards as a consequence of the wall. The fragmentation and isolation of their commu- nities have been aggravated. In short, the Palestinians have become caught in a fishnet of Jewish settlements, bypass roads, check- points, and military patrols—walled in and walled out. Fear, insecurity, and a tremendous waste of time are their daily lot. With a state like this, who needs apartheid?

Fragmentation and severe restrictions on the mobility of people and goods have turned the Palestinian economy into a series of micro-economies attached to the Israeli econ- omy. Israeli control over international ports prevents direct linkage of Palestinian markets to Arab and international markets, except through Israeli mediation. A Palestinian state would thus be missing a critical component of statehood: a unified national market joined directly to external markets. A viable state cannot evolve without such a market.

Why did Israel force the Palestinians into this corner? Why did it keep expanding settle- ments and building bypass roads after Oslo? Why did it continue its tight control over the international ports and impede the movement of goods to and from Jordan? Why did it refuse to build a safe passage between Gaza and the West Bank? Why did it, during the pre-Oslo negotiations held in Washington, D.C., stubbornly refuse to demarcate the borders of the settlements and agree to a functional role over them, as the Palestinian delegation headed by Dr. Haidar Abd Al- Shafi had consistently demanded? There is only one explanation: Israel has never accepted the idea of a viable, sovereign Pales- tinian state.

We must recall that before the 1991 Madrid conference Israel had traditionally rejected the idea of a Palestinian state on the grounds that it would be unviable. In an attempt to rebut this thesis, and shortly before the conference, the Institute of Palestine Studies in Washington, published a mono- graph by economist George Abed, The Economic Viability of a Palestinian State. Abed argued that a Palestinian state in the entire West Bank and Gaza would be viable, given that certain economic and political conditions were fulfilled. If the viability of a Palestinian state was contested before Oslo, when Jewish settlements were more sparse than today and the bypass roads and wall were not yet built, surely the debate now has been laid to rest. Israel used what was meant to be a transitional period to Palestinian statehood to render such a state all but impossible. Forget about the “generous offer” of Prime Minister Ehud Barak to President Yasser Arafat at Camp David, for it meant that Israel would take away only a bit more land on top of the 78% of Palestinian land it had come to control after 1948 and would remain the virtual gatekeeper of the borders of any Palestinian state. Forget, too, about differ- ences between Labor and Likud. Construc- tion of Jewish settlements and land seizure was even greater under Labor than under Likud. Shimon Peres, ever the wolf in sheep’s clothing, rescued Prime Minister Ariel Sharon at critical moments whenever the latter found himself constricted in political bottlenecks. The major political forces in Israel want the Palestinians out.

What, then, is to be done?

Even a viable state in the West Bank and Gaza, I think, would not resolve the Palestin- ian Question. We would still be left with the Palestinians who are Israeli citizens, unable to be integrated into a state that insists on being a “Jewish state.” There is not only the Palestinian Question; the Jewish Question, too, still lingers on. And there would be Pales- tinian refugees who legitimately demand the right to return to the territory from which they were evicted. Israel exhibits no sign of consenting to such a demand. That would leave us in Greater Palestine with the Jordan- ian Question, too. For if the refugees remain in Jordan, East Jordanians, whose identity the Jordanian monarchy fostered by pitting them against the Palestinians, would be afraid that sooner or later the Palestinians would take hold of the reins of power. The establishment of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza would intensify their apprehension. The threat of instability would be ever present in the kingdom.

The Palestinians nation has fallen a great fall, and the time has come to put it together again. The Palestinians need to do something that has not been done before: they must tap their demographic advantage. Oslo demobi- lized the Palestinians outside, and Israel’s recent disengagement from Gaza will slowly demobilize its population. Years of isolation under Israel’s dominion tied the West Bank elite to Israeli and Western counterparts, perhaps more than to the Palestinians outside. The segment of the PLO that entered the West Bank and Gaza got busy consolidating its position and ignored the diaspora. “Realist” politicians and intellectuals from both groups began to find it easy to bargain away the right of return of the Palestinian refugees in the naive, if not self-serving, belief that such a give-away would win them a state.

Why should the people who constitute the majority in Greater Palestine be without a state, dispossessed and oppressed by Israel and made sub-citizens by successive Jordan- ian regimes? The time has come for a new vision and a commensurate strategy that would mobilize the Palestinians in Israel, the West Bank and Gaza, and Jordan to create a single state in Greater Palestine that would include themselves, East Jordanians, and Jews. The Palestinians have consistently acquiesced and diminished their aspirations, while the Zionist movement and Israel have inflated theirs. They have been too polite, too soft in their demands. Their adversaries thought and acted out the outrageous and the unthinkable. The Palestinians need now to think out of the box, out of the fishnet, out of the cage.

A trinational state in Greater Palestine (a mutually acceptable name for the state could be agreed on through discussion) has many advantages over the other theoretical alterna- tives: East Jordanian, Jewish, and Palestinian states; a binational state in Western Palestine and an East Jordanian state; or a Jewish state and a Palestinian-Jordanian state in Transjor- dan, the West Bank, and Gaza, as existed between 1948 and 1967.

It would be large enough for everybody; no one has to be squeezed out. It would allow people to move into places where their spirit, their heart, or their pocket feels at home. The right of return of the Palestinian refugees would become largely superfluous. The Jews would live in Eretz Israel, the Palestinians in Greater Palestine, and East Jordanians in Jordan, and those who hail from cities like Hebron and Nablus could, if they so wish, reunite with their roots. With my sincere admiration for Jordan’s historical heritage, I should think that it would be loftier for East Jordanians to belong to a state that encom- passes Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and Nazareth. For millennia, Jews coexisted with Arabs and Muslims and thrived economically and culturally in their midst. The creation of Israel disrupted an admirable, long-shared cultural history, as Ammiel Alcalay wonderfully demonstrates in his After Jews and Arabs: Remaking Levantine Culture. It relegated Israel’s “Oriental Jews” to an inferior position relative to that enjoyed by Jews of European descent. Anti-Semitism is a European demon. Why has Zionism chosen to make Jews feel that they belong more to the cultures of their oppressors and annihilators than to those in which they lived fairly amicably? Not least of the virtues of a triethnic state, a large popula- tion means a large market, nothing to scoff at in today’s highly competitive world economy. Shimon Peres propagandized after Oslo for a New Middle East. The current Bush adminis- tration introduced to the agenda a Greater Middle East. Why not start more modestly, with Greater Palestine?

Of course, there are many obstacles and deep-rooted resentments. Israelis, it will be said, will not accept such a seemingly radical suggestion. True, but when in 1974 Yasser Arafat proposed before the UN General Assembly a democratic secular state in West- ern Palestine, Israel said that this was a disguised plan for its destruction. Neither are there many takers in Israel today for the bina- tional state idea that is increasingly gaining support among Palestinian intellectuals. The creation of a unitary state in Greater Palestine is no different in its requisites than that of a bi-ethnic state in Western Palestine, and it has the advantage of not leaving the Palestinian refugees out in the cold or Jordan unstable. Both are historic projects and require much thought, planning, organization, and persuasion.

The vision of a single state in Greater Palestine could come to fruition only through a strategy of Palestinian mass mobilization, non-violence, and dialogue with the other two communities. Violence must be relegated to the dustbin of history. The Palestine Libera- tion Organization (PLO) needs to reconsti- tute itself into a revitalized and vital Palestine Reunification Organization (PRO). A new leadership must emerge, and the old thinking must be jettisoned.

This applies to Israel as well. The course it has pursued is one-eyed (my apologies to the one-eyed). It places too much faith in force and the power of arms, and it suffers from an unhealthy dose of hubris. It may have won Israel a dunam here and a dunam there, but it has embroiled it in interminable warfare. There are no signs that this will change in the foreseeable future. The Hashemites began their career on a high note of pan-Arabism, which has shrivelled to the parochial and divisive “Jordan first.” They and Zionism divided up Greater Palestine and undertook to suppress Palestinian national- ism. In the process they created a deep Pales- tinian–East Jordanian cleavage that keeps the two peoples suspicious of each other. But both they and the Israelis are still in denial, believing that somehow, someday, they can contain the Palestinians. They both need to see this approach for the mirage that it is. They made a formal peace with each other, and now they must both do the same with the Palestinians.

The Palestinians committed their own share of mistakes along the way, and were not entirely blameless. The time has come for them to get out of the tunnel in which the big news has been the next date on which Sharon will refuse to meet Abu Ammar or Abu Mazen. A mini-state never inspired the Pales- tinian collective; how could a state comprised of fragments? The Palestinians need a new source of energy, a new vision. When Jews were debating the boundaries of Palestine early in the 20th century, an extreme Zionist, whose name I cannot recall at the moment, said that the Jordan River did not divide the two banks, it united them. I agree with this insight, absent the man’s bigotry. A single state in Greater Palestine is the sane alterna- tive to internecine conflict and despair, for all its inhabitants.

Notes

1The author was a member of the Palestinian delegation in the Land and Water Working Group in the 1993 bilateral negotiations with Israel held in Washington, D.C.

2Roughly 2.7 million in the West Bank, 1.3 million in Gaza, 1.3 million in Israel, and 3.25 million in Jordan (or 60 % of the total population, which is the commonly cited ratio). These figures are based on the depart- ment of vital statistics in each entity.

3Refugees of the 1967 war.

References

Abed, G. 1990. The Economic Viability of a Palestinian State. Washington, D.C.: Insti- tute of Palestine Studies.

Alcalay, A. 1993. After Jews and Arabs: Remak- ing Levantine culture. Minneapolis: Univer- sity of Minnesota Press

Childers, E. 1971. The worldless wish: From citi- zens to refugees. In The transformation of Palestine: Essays on the origin of the Arab- Israeli conflict, ed. I. Abu-Lughod, 165-202. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Khleifi, M., and Sivan, E. 2004. Route 181 frag- ments of journey to Palestine, Israel