-

Proposal for a visual media exhibition

with the participation of students of the Master of Film at the Dutch Film Academy, Amsterdam -

Get my films

Buy DVDs online at www.momento-films.com -

IZKOR

slaves of memory

Documentary film | 1990 | 97 min | color | 16mm | 4:3 | OV Hebrew ST -

Common Archive Palestine 1948

web based cross-reference archive and production platform

www.commonarchives.net/1948 - Project in progress - -

Montage Interdit [forbidden editing]

With professors Ella (Habiba) Shohat and Robert Stam / Berlin Documentary Forum 2 / Haus der Kulturen der Welt / June 2012 -

Route 181

fragments of a journay in Palestine-Israel

Documentary film co-directed with Michel Khleifi | 2003 | 272 min [4.5H] | color | video | 16:9 | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST

-

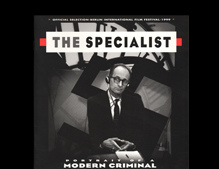

The Specialist

portrait of a modern criminal

Documentary film | 1999 | co-author Rony Brauman | 128 min | B/W | 4:3 | 35 mm | OV German, Hebrew ST -

Jaffa

the orange's clockwork

Documentary film | 2009 | 88 min | color & B/W | 16:9 | Digital video | OV Arabic, Hebrew, English, French ST

-

Montage Interdit

www.montageinterdit.net

Web-based documentary practice. A production tool, archive and distribution device | project in progress

-

Common State

potential conversation [1]

Documentary film | 2012 | 123 min | color | video | 16:9 split screen | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST -

Towards a common archive

testimonies by Zionist veterans of 1948 war in Palestine

Visual Media exhibition | Zochrot Gallery (Zochrot visual media lab) | Tel-Aviv | October 2012 - January 2013

-

I Love You All

Aus Liebe Zum Volk

Documentary film co-directed with Audrey Maurion | 2004 | 89 minutes | b/w & color | 35mm | OV German, French ST

The Specialist (Eyal Sivan ; France, Israel, Germany, Belgium, Austria, 1998,128 min.) AdoIf Eichmann, SS Lieutenant Colonel, a specialist in the transportation of freight via railroad ; was hanged in Israel on May 31, 1962, aged fifty-five. This film traces Eichmann’s life, ending with his trial in Jerusalem for crimes against humanity, and other offenses. Eichmann was born in the Rhineland, 1906, and as a child moved with his family to Linz, Austria. From aged seventeen, he worked as a miner, trainee in electrical construction and salesman. At twenty-six, he joined the Nazi party and the SS. The next year, as Hitler took power, Eichmann returned to Germany, served in the army for a year, followed with special SS training. ln 1934, he transferred to Berlin for duty within the SS Freemason Investigation Department. In 1935, Eichmann joined the SS Jewish Affairs Department, learned basic Yiddish and Hebrew. He married and would father four children. He was promoted to second lieutenant, 1936, and two years later, he was sentback to Austria, following the Anschluss that united Germany and Austria. He began organizing the forced emigration of Jews from Austria. In 1940, the year after the war began ; he studied a plan for the mass deportation of Austrian Jews to the island of Madagascar, off the southeast coast of Africa, a plan never realized. In 1941, Eichmann was named head of IV-B-4, a department charged with "Jewish Affairs and Evacuations". He held that position until 1945, with new rank of SS. Lieutenant Colonel. In 1942, he attended the SS Wannsee Conference, near Berlin, to discuss "The Final Solution to the Jewish Problem." The meeting was headed by Reinhard Heydrich, number-two after Heinrich Himmler ; Iater assassinated by Czech commandos in Prague. 1945, the war ended, Eichmann was briefly a war prisoner, under a false name, and escaped, twice eluding capture. He spent the next four years in West Germany, during the Nuremburg Trials, until travelling in 1950 to Austria, Italy and Argentina ; he lived there with his family, using the name "Ricardo Klement". After ten years in Argentina, Eichmann was captured on May 11, 1960, by the Israeli Secret Service ; two days later, David Ben Gurion announced that Eichmann was in Israel to face trial. The trial began April 11, 1961, guilty sentence was passed on December 15 : "This court condemns Adolf Eichmann to death for his crimes committed against the Jewish people, for his crimes against humanity and for his war crimes." Eichmann appealed, but sentence was confirmed on March 28, 1962. Eichmann petitioned the Head of State for a reprieve, asking for mercy, but it was refused on May 31, 1962. That midnight, Eichmann was hanged. His ashes were dropped into the Mediterranean, outside Israeli territorial waters.

Prosecutor of Eichmann, and by extension the whole Nazi movement was Giddeon Hausner, whose opening speech lasted three days, presenting himself as the voice of the six million Jews killed during the Holocaust. Eichmann’s attorney was Robert Servatius, from Cologne, formerly an assistant at the Nuremberg Trials. Hired by Eichmann, he was paid by the Israeli government. Seemingly overwhelmed by the evidence against Eichmann, Servatius was ineffectual ; thus Eichmann carried out his own defense. The three Israeli judges were of German origin. Chairman Moshe Landau strove for legal decorum _"clear answers to precise questions"_ emphasizing Eichmann’s personal responsibility. Judge Benjamin Halevy often addressed Eichmann in German and, in effect, was his "confessor". Judge Yitzhak Raveh aIso spoke German to the defendant. These two judges were able to elicit significant information from Eichmann about his role and methods. The trial covered eight months in 1961 and took place in the main auditorium of the House of the People, Jerusalem, transformed into a courtroom for this trial. ln the trial, many survivors from Auschwitz and other camps testified emotionally as to what occurred.

The prosecution characterized Eichmann as a bloodthirsty pervert, a Machiavellian liar and serial killer, a quiet family man both comic and terrifying in his banality. Hausner rejected Eichmann’s defense that as a specialist he merely obeyed orders originated by his superiors. Hausner emphasized that Eichmann was the former head of the SS IV-B-4 bureau handling the inner security of the Third Reich, thus in charge of the mass deportation of Jews, Slovenes, Poles and Gypsies to the death camps. Eichmann’s defense was that he was merely the executor of a criminal law that he disapproved of inwardly : he was guilty of his obedience. This is a defense heard often in courts today, worldwide, deflecting personal guilt, claiming to be a mere pawn in a fragmented decision-process that easily lends itself to the erasure of all notion of responsibility. These are "public service crimes," e.g., by civil servants, technicians, scientists, employees, aIso those in the military committing atrocities _each is carrying out his/her tasks at their individual level, applying their routine procedure to solve practical problems, not moral problems. ln Eichmann’s case, his assignment was to move cargo by railroad to its destination_ pure logistics. The reality of these horrors is disguised or diminished by the euphemistic vocabulary used : evacuation, transfer, operations, special treatment, and final solution. The technocrat’s moral crime, if disguised and thus repressed, hidden from awareness, allows the technocrat to function. The ordinary person, Iike Eichmann, is guilty of an extraordinary crime yet cannot recognize it, thus rejects claims of responsibility. Hannah Arendt points out of Eichmann _"his normality is much more terrifying than all atrocities together"_ a theme she explores as "the banality of evil." Thus Eichmann on trial insists on his powerlessness ; he’s "a drop in the ocean, a tool in the hands of superior powers." If he didn’t obey, others would replace him. But he confesses that he knew the contents of those box-cars, people rounded up "on account of their race," he admits he supplied the death camps with "contingents for destruction". At the Soviet front, he witnessed mass executions, Jews forced into a ditch and machine-gunned, some were mothers with children. He acknowledges a conflict of his professional duty versus his moral conscience, but no one can accuse him, he claims, of doing a bad job. "I did my job well."

Near the trial’s end, The Specialist shows Eichmann conceding that he thinks blind obedience to authority, theories of racial superiority, "nationalism carried to extremes," all that can mislead people. "On human terms, I am guilty" and "ln my conscience, I am guilty". He states that he intends to write a book about all that, after the trial.

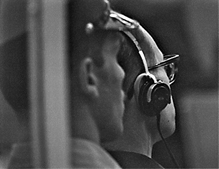

The Israeli government determined to preserve a visual record of the Eichmann trial and to film it in its entirety _unlike the Nuremberg Trials, where only chosen moments were filmed. Television was in its infancy, and this was to be the first TV production shot on actual location, the special Eichmann courtroom. Lacking experienced technicians and facilities, the Israelis turned to ABC-TV, Capitol Cities, and the American documentary director Leo Hurwitz, whose U.S. credits included Strange Victory, Native Land (with Paul Strand), editor of The Spanish Earth, narrated by Ernest Hemingway, cameraman of the Plow that Broke the Plains, by Pare Lorentz, later Director of Film Production, New York University. Hurwitz built four platforms within the courtroom, behind which cameras did their work. The four images went to a central control-room, where one of the four images was preserved for the film _thus presumably the other three images were erased, and _presumably_ Hurwitz made these selections.

With great difficulty, producers of The Specialist got permission from the Israeli government to gain access to the surviving trial footage _then special pioneering videotapes. Housed badly for over a third of a century, much footage and sound material were defective ; also records were undependable ; and they had difficulty finding technology today that could handle such old materials. ln 1977, much of the tapes in the U.S. returned to the Steven Spielberg Jewish Film Archives at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Because of space problems there, the materials were stored in an unused washroom. "The Spielberg Archives immediately decided to extract a selection of seventy-two hours," notes the press materials for The Specialist. "Of these seventy-two hours of film, recorded onto poor quality tape and presented not as copies but as originals, a few sequences were regularly sold." The footage provides a special insight into the Nazi death machine that no other war crimes trial had previously attained. Of five hundred hours of video shot, much was unusable. At the end of the trial, a ton and a half of tapes were shipped to New York and forgotten for fifteen years. Producers of The Specialist faced great obstacles _technical, financial and bureaucratic. From five hundred hours of picture, to three hundred fifty, to seventy, to twelve, to eight _the producers labored to find a form within a shapeless mass. Long, complicated, innovative processes were devised, for both sound (six hundred hours) and picture. At length, 35mm prints were struck, and the film was screened at the Berlin festival in February.

Director/producer Eyal Sivan is an Israeli dissident working in France since 1986 on the displacement of Palestinian populations and other topics. Within Israel, quoting press materials, "The omnipresent name Eichmann has special resonance and is used to cement national unity. The issue of total obedience to orders, the central object of discussions in Israel since the Lebanese war of 1982 and during the years of the Palestinian uprising, the Intifada, in the lands occupied by the Israeli Army, all that served to strengthen Sivan’s interest in the Eichmann material."

Co-writer with Sivan, Rony Brauman has vast experience in relief work, c.g., the Ethiopian famine of 1985, the Rwanda genocide of 1994, and other abominations that feed on man’s destructive passions and engage his consent He has published and lectured widely, and for twelve years was Chairman of the international relief organization, Medecins sans Frontieres.

GORDON HITCHENS is Contributing Editor to International Documentary. He was founding editor for Film Comment’s first seven years. As a stringer for Variety, he’s reviewed more than 200 films for the newspaper. A former faculty member at C.W. Post/Long Island University, he serves as consultant to numerous film festivals throughout the world, including Berlin and Yamagata.